In The Beginning There Was Wally

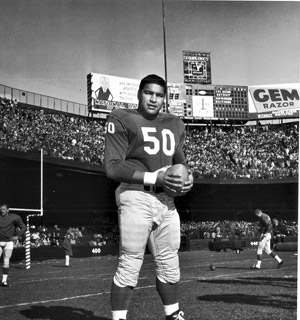

Wally Yonamine with the San Francisco 49ers. Photo courtesy Jane Yonamine Colorized by James Nakamura

During the National Football League’s Pro Bowl Jan. 27 at Aloha Stadium, for the first time the NFL will honor former players from Hawaii. Dubbed the Hawaii NFL Legends, the seven were chosen by the local Pro Bowl host committee, based on performance, accomplishment and character on the field and off it. MidWeek is pleased to have the exclusive on this inaugural class of honorees: Wally Yonamine, Herman Wedemeyer, Charlie Ane, Arnold Morgado, Jim Nicholson, Blane Gaison and Leo Goeas

Wally Yonamine was first. In so many ways.

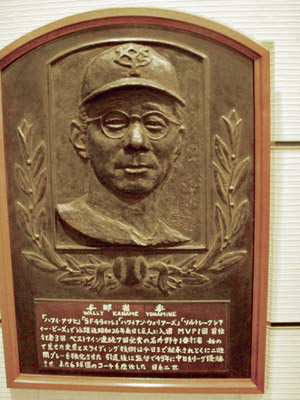

As the National Football League prepares to honor seven Hawaii men who made it in professional football, Yonamine is first among them. The Farrington High alum is the first athlete of Hawaii birth, and the first person of Asian ancestry, to play pro football at the highest level. Yes, the man eternally enshrined in the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame, and for whom the Hawaii high school baseball championship tournament is named, first played for the San Francisco 49ers.

Which turns out – as history-changing and dreams-altering as it was for so many people – to be almost the least of Yonamine’s firsts.

While this is much more than a sports story, it does affirm the transformative power of sport, and of boyhood dreams. And it’s a story that set the stage for the many young men who were to follow in his cleat marks. How many? The website databaseFootball.com lists 67 local boys who have played in the NFL. Wally Yonamine led the way.

(A brief aside regarding historical firsts: “Honolulu Johnnie” Williams, of native Hawaiian ancestry, pitched four games for the 1914 Detroit Tigers, making him – it is believed – the first island-born athlete to play in a major U.S. professional league. Walter Achiu did play the 1927-28 seasons for the NFL’s Dayton Triangles after attending the University of Dayton, but the NFL of those days was far from a major league.)

It was 1947, and wars in the Pacific and Europe were barely two years ended. In San Francisco, emotions were still raw as thousands of Japanese – most of them American citizens – who had been rounded up and forced from their homes and businesses in The City’s thriving Japantown returned from desolate internment camps.

In Wally Yonamine, San Francisco 49ers rookie running back, they found a dashing young hero on whom they could hang their new hopes.

“He made us proud that we were Japanese,” Hats Aizawa remembered nearly 50 years later. Quoted in the English-language Bay Area newspaper Nichi Bei Times in 2005, Aizawa, 77, who had attended Yonamine’s games at Kezar Stadium with other young nisei (second generation), continued: “He had this burst of speed … he was fast. He left me with a lot of pleasant memories.”

The paper also quoted Warren Eijima, 81: “To see another Japanese-American play made me feel good.”

So Wally was a powerful symbol for Japanese rebuilding lives and businesses – many having found strangers of other ethnicity now living in homes and running stores and restaurants they’d been forced to abandon. In that, he was also first.

“Wally always said he had to do well because of all those from the internment camps coming back to San Francisco who were rooting for him to do well,” his widow Jane recalls.At the same time, for many San Franciscans who served in the war or lost a loved one in it, and referred to Japanese people by the J-word, he was also a symbol that the war was over. Here was a Japanese man for whom they could stand and cheer. They were now on the same side. That too was a first.

For both groups, Yonamine’s presence in a 49er uniform was a turning point of sorts.

As a 49ers reserve running back in the autumn of ’47 (the team’s second year of existence), he started three games and averaged 3.8 yards per carry and 11 yards per pass reception for Coach Buck Shaw. As a defensive back in those days of ironman two-way players, Yonamine had one interception.

“Football, that was Wally’s first love,” Jane says. “That was the only sport he ever really loved. Years later, when people asked about the old days, the first thing he mentioned was football.”

Looking ahead, he and the 49ers had every reason to be optimistic about the 1948 season.

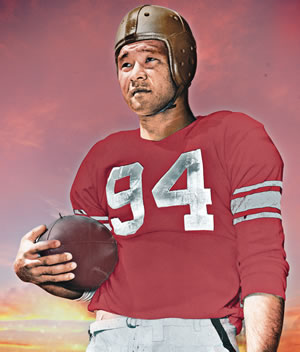

(In those years, the 49ers – wearing snazzy red-and-white uniforms and leather helmets – played in the eight-team All-American Football Conference, which stretched from New York to Los Angeles. In 1950, the Niners along with franchises in Cleveland and Baltimore joined the NFL, breathing new life into the league, much as the NFL-AFL merger would do a generation later.)

It started on the sugar plantation at Olowalu, Maui. Born Kaname Yonamine on June 25, 1925, the boy who would become “Wally” was the third of seven children born to Okinawa-born Matsusai Yonamine and Maui-born Kikue Nishimura, whose parents had emigrated from Hiroshima. (In Japanese, kaname is the single nail that holds a fold-out fan together. “And that’s who he was,” Jane says.)

Despite his father working hard from dawn to dark on the plantation, and being promoted to a variety of better jobs, life remained hard, and putting food on the table for a growing family a challenge. The family was so hard up, Wally recalled later, “my parents couldn’t afford to buy us a stick of candy.”

Likewise, there were no toys. So he and his brother Akira ran around, literally. Akira, two years older, was the fastest kid on the plantation, and Wally was right behind. Akira’s Maui record for the 40-yard dash stood for decades.

The authoritative 2008 book Wally Yonamine: The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball by Robert K. Fitts (University of Nebraska Press) includes an anecdote about the hungry, adventurous Yonamine boys stealing a watermelon, despite getting fired at by a shotgun-toting farmer. They soon gravitated to sports, whatever the season was.

“He was a rascal,” Jane says. “Nothing really bad. Mostly, Wally was so busy with sports, he didn’t want to do school-work.”

That is how, out of seven siblings, he was the only non-Buddhist.

“His uncle took him to the Catholic church to straighten him out,” Jane says.

His faith stayed with him, which is one reason he and Jane bought a unit at Kahala Nui retirement center, so he could walk to morning mass every day at adjacent Star of the Sea church.

In his book, Fitts writes “the Yonamine brothers played softball, volleyball, soccer and Wally’s particular favorite, football. Since they didn’t have enough money to buy a football, they took an (empty) can of Carnation creamed corn, wrapped it in newspapers, and used that instead.” And because there were few teen boys in the area, the Yonamine brothers joined men’s games.

A radio was Wally’s first window into a world beyond plantation life, and he especially enjoyed listening to games of the semi-pro Hawaii Baseball League and ILH football games from Honolulu Stadium. Listening to games, often with his grandmother, he began to dream of playing in the big city.

As a teen he worked summer days on the plantation, cutting sugar cane.

“I used to really hate that job,” Wally told Fitts. “I got paid only 25 cents a day, but it was the only job I could find. I told myself I never wanted to work in the cane fields again. That’s where my drive to always try my best and never give up came from.”

Wally boarded at Lahainaluna High School for his freshman year, and with other boarders worked three hours on the school farm before classes. His job was to personally bring in 100 pounds of grass a day for the farm’s cows. He went out for the football team in that autumn of 1941 and was named to the second team. But in the first game – against Roosevelt of Honolulu – a Lunas running back broke his thumb, and the coach put in Wally. On his first play, after taking a lateral pitch, Wally threw a 35-yard touchdown pass. He later ran 11 yards for another TD and scored again on a 70-yard interception return.

The Lunas went 6-0 on Maui and hosted Oahu champions Saint Louis in the Haleakala Bowl, which drew 4,000 spectators to the Kahului Fairgrounds. The star for Saint Louis was “Squirmin’ Herman” Wedemeyer – as it happens another inaugural inductee into the Hawaii NFL Legends. The city boys prevailed with two late scores, 13-0.

Wally again worked the sugar fields the following summer and returned for his sophomore season at Lahainaluna. With him running and passing out of the single-wing formation, and kicking, punting and returning kicks, the Lunas again won the Maui title, going 5-0-1. In the deciding final game, Wally scored all 19 points in a 19-6 win over St. Anthony.

On Maui, he was the best player on any field stepped, but he couldn’t get the dream of playing in Honolulu Stadium out of his head. So he asked his father if he could move to Oahu. Having himself left Okinawa at 17, Matsusai said, “If you want to go, you go.”

He went, moving in with an older sporting friend from Olowalu, Mac Flores, now a stevedore.

Wally could have attended Saint Louis – just picture him in the same backfield with Squirmin’ Herman – but instead enrolled at Farrington in the fall of 1943. It was there Kaname adopted the name Wally – after the school’s namesake, Gov. Wallace Rider Farrington. It was frustrating having to sit out his junior year after transferring, and he was never sure where his next meal would come from, but he worked out regularly with Farrington equipment manager Arthur Arnold (who’d also suggested the name change as a way of fitting in) and was ready for his senior season.

Imagine his thoughts and emotions as he ran onto the field for his first game at Honolulu Stadium, which at capacity held 26,000 spectators, his boyhood dream about to come true. Kamehameha was the foe, and wearing a white No. 37 Govs jersey Wally kicked a field goal to open the scoring, later prevented a Kamehameha score with an interception, scored on a run early in the third quarter and added the extra-point kick, giving Farrington a 10-7 win. As in his final game on Maui, in Wally’s first game on Oahu he tallied all the winning points. He would repeat that feat several times during the season, and was named the Honolulu Advertiser‘s league MVP.

Wally turned 20 the following summer and was drafted into the U.S. Army. But the war in Europe was over and Japan would surrender six weeks after he started basic training at Schofield Barracks. It was there he caught the eye of Pittsburgh Steelers coach Jock Sutherland, who had played college ball at Pitt under the legendary Pop Warner. Sutherland offered Wally a contract with the Steelers, but he declined, saying he wanted to attend college – he had scholarship offers from USC, Ohio State and St. Mary’s (where Wedemeyer was starring).

Meanwhile, he joined a local all-star team that scheduled a tour of West Coast universities. He starred in the first game, at Portland’s Multnomah Stadium, impressing a 49ers scout who was actually there to watch Hawaii-born Portland quarterback Charles Kawainui Liu. Three games in California followed, and the number of scouts showing up to watch Wally grew with each. In the spring of 1947, he accepted the offer from Ohio State. Preparing to leave, though, he was invited by 49ers coach Buck Shaw to come to San Francisco for a tryout. Shaw was impressed, and offered a two-year, $14,000 contract. That was big money in 1947, and his parents were still laboring at Olowalu. Deciding, “I ought to help the folks,” he became a 49er.

As Robert Fitts writes: “Wally would never have to work on the plantations again.”

But his football days were numbered.

Returning home after his first promising season in San Francisco, Wally went to work for a trucking company, thinking the lifting and carrying would strengthen him. He also played AJA baseball for the Athletics (later to become Asahi). He fractured a thumb sliding into a base in an exhibition game at Hilo, and reported to the 49ers with a cast on his hand. With him unable to play, and with the 49ers having just signed another speedy running back – future Hall of Famer Joe “The Jet” Perry – the team voided the second year of Wally’s contract, costing him $7,000.

Fitts reports Wally was “disappointed, really sad. Football was the sport I really loved. In the off-season, I just fooled around with baseball.”

Not ready to give up football, he signed with the Hawaiian Warriors of the Pacific Coast Pro Football League for the 1948 season. While Wally again starred on the field, the league was failing at the box office, and it folded before season’s end.

He was invited to the 49ers training camp in 1949, but despite flashes of brilliance was cut. Back in Hawaii, he again joined the Warriors, who were embarking on an East Coast barnstorming tour. Playing against the Patterson (N.J.) Panthers, Wally intercepted a pass and during the runback was crushed from behind by a much larger player, badly dislocating his left (throwing) shoulder. His days of throwing a football 70 yards on the fly were done.

And with that, Wally’s football career was finished too. He turned to baseball, with a huge helping hand from former big-leaguer Lefty O’Doul. His ties to Japanese baseball went back to 1931 when he was part of a touring Major League all-star team, and like so many gaijin fell in love with the country and its people. Following the war, he returned to Japan several times to help reinvigorate the game, including managing the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League during an exhibition tour in 1949. Passing through Honolulu on the way home, he heard about a promising young player. Thus Wally was invited to join O’Doul’s Seals for spring training. “Wally has a perfect swing,” O’Doul told reporters, “and he’s strong.”

He wound up in Salt Lake City, where he starred, and after the ’50 season O’Doul helped arrange for Wally to sign with the Yomiuri Giants in Tokyo.

He joined the Giants for the 1951 season, and succeeded from the start, reminiscent of his debut football games for Lahainaluna and Farrington.

In his first at-bat for the Giants, he bunted for a hit. On the ensuing play, sliding with spikes up to break up a double play, he knocked the shortstop down. This was shocking to fans and players, because the norm for Japanese runners was to veer into right field, politely conceding the out at second base. And when Wally drew a bases-on-balls, he ran to first base, just as he sprinted to his position in the outfield – foreign practices for Japanese players then.

He’s been called the Jackie Robinson of Japanese baseball, and with good reason, though as Wally said later, “the difference is that I was the same color they were, and I couldn’t speak the language.” Wally was initially loathed for his aggressive American-style play. He was cursed because he was American, and as a nisei had not returned to the Motherland to fight – worse, he’d served in the U.S. Army and was “the enemy” for many fans and several teammates who’d served in the Imperial military during the war. Taking his place in centerfield, rocks were thrown and landed at his feet, but he never responded, Robinson-like in his determined calm. Teammates often ignored him. But he persevered, leading the Giants to the Japan title, homering in the clinching game. For the season, he hit .354, stole 26 bases in 30 attempts, and scored 47 runs in 54 games.

That would open the door for other Hawaii boys to play in Japan, including his friends Jyun Hirota and Dick Kitamura, and more than a thousand Americans have since played in Japan. Yonamine would play 12 seasons in Japan with a career .311 batting average, retire as a beloved hero, earn a place in the Japan Hall of Fame as both player and manager, and be honored by the Emperor with the Order of the Sacred Treasure, the first professional athlete to be so cited.

And he did it in an aggressive style he first learned on the football fields of Hawaii.

He also did it in a quiet, local-boy style that seems to have created the model for the humble heroics of Oregon’s Marcus Mariota and Notre Dame’s Manti Te’o this season, among many other Isle athletes at colleges large and small, and in the NFL.

“I’m just a boy from Olowalu,” Wally told Fitts. “I’ve never forgotten my roots and where I started … People tell me I’m a living legend and a big star, but inside I don’t feel I’m any different from anybody else. I’m just one of the guys – the same person I was growing up. I’ve been fortunate, and I’m just happy I can give something back to Hawaii and help others fulfill their dreams.”

Did he ever.

Wally Yonamaine died Feb. 28, 2011, after a long battle with prostate cancer.

For more on Wally Yonamine and his wife Jane, see Page 19 or click here

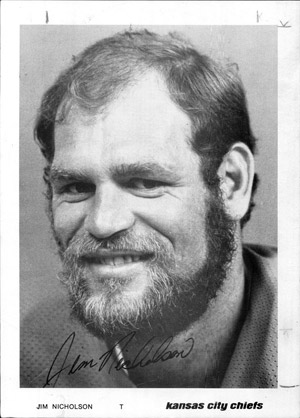

Jim NicholsonJim Nicholson misses the laughter. Not just the smirks and chuckles from random jokes, but the big belly laughs that spread throughout the locker room on a daily basis. It’s a fitting memory for the former offensive tackle who can’t seem to go very long without breaking out into smile and a laugh.

“I’m not talking about laughing, but having a laugh where your stomach is hurting. You were guaranteed that because someone was always doing something,” says the Saint Louis alum (where he also was a basketball star) without a moment’s hesitation.

Nicholson’s career began at Michigan State in the days when Spartan coach Duffy Daugherty had a near lock on top Hawaii talent west of the Rockies. While there, “Big Nick” learned how delicate a large body can be.

Coming into his sophomore year, Nicholson was the starting tight end and looking for a big year. Instead, his knee blew out on his first catch of the season. He was moved to defense, where a back injury forced another position change, this time to offensive tackle – and the only healthy playing year of his college career. Even with all that, Nicholson was drafted by the Rams in 1973 and sent to Kansas City the next year, where he spent six years before his career started to wind down and the next chapter of his life began.

“I played one game in San Francisco the year they won the Super Bowl. But at the same time I was accepted into law school. You go from being with the Chiefs for six years to San Diego for a year, then San Francisco and put on waivers, it’s time to start looking for work instead of collecting T-shirts. It wasn’t a hard decision.”

It also wasn’t hard to find inspiration to tackle his next career.

“My roommate was Tom Condon, the super agent who gets all the top draft picks every year, and when we were playing ball he went to law school. I figured he couldn’t even remember the snap count, if he can do (law school), I can do it too,” says Nicholson with a big laugh. “I found out it wasn’t that easy.”

Today, Nicholson is the head of the state Labor Relations Board. It’s safe to say things worked out.

-S.M.

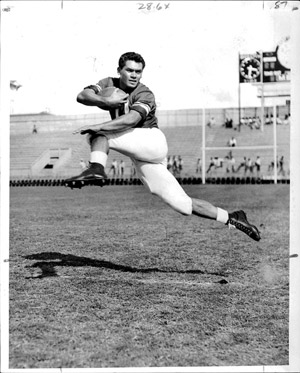

Herman WedemeyerHerman Wedemeyer never would have made it in today’s NFL.

In a league where specialization has become the norm with third-down backs and nickel packages, where a superstar like running back Adrian Peterson asks to also run back punts and gets laughed out of the building, there is no room in such a league for the original Flyin’ Hawaiian.

In 1945, he was an unanimous All-American for his St. Mary’s team, filling a stat sheet in a way that the modern player could never understand: third in total offense, fourth in punting, fourth in passing – and all while being the starting safety for the team.

But how does one become an all-around football player like this, a decathlete with pads?

It started with his roots, playing football on his native Big Island, a rudimentary version of the game where there sometimes would be 30 guys aside. It was during his small-kid times, having to dodge more than two dozen defenders, that he learned the moves that would later earn him his litany of nicknames: Squirmin’ Herman, The Hawaiian Centipede and The HulaHipped Hawaiian.

His diversity developed from necessity. When he enrolled at St. Mary’s in 1943 after starring at Saint Louis, the team had 20 players, 17 of whom headed off to war in the fall. So the coach created a team of 17-year-olds – too young for the draft. While the results were not stellar, young Wedemeyer became a star.

He spent a year in the merchant marines in 1944, but his return to school in ’45, which had a total enrollment of 142 men because of World War II, marked a historic year in Gael football as Wedemeyer led them to a 7-0 start, with wins over such powerhouses as USC and Cal. This caused local papers to proclaim Wedemeyer as “the most sensational discovery to come over the horizon since the Santa Maria.”

He finished fourth in the Heisman vote that year, and but for a crushing 13-7 loss to UCLA in the final game of the season, had his team vying for a national championship.

That season earned him a spot in the College Football Hall of Fame and a spot as the first round draft choice of the Los Angeles Dons of the AAFL.

But the pro game didn’t attract him with the variety of positions that he had in the college game, and after a season with the Dons and then a season with the Baltimore Colts, he called it quits to come home to the Islands.

He kept up the diversification of his life, entering the political arena and serving on the City Council and in the state Legislature in the late ’60s and early ’70s. He also starred on the original Hawaii 5-0 as Ed Lukela from 1971 to 1980.

Wedemeyer died Jan. 25, 1999, but every generation of local gridiron greats owes a debt to him and the trail he blazed from the middle of the Pacific to the Hall of Fame.

His nephew Blane Gaison is also a member of this class of Hawaii NFL Legends.

-Chad Pata

Most of us can’t understand Arnold Morgado’s feelings about the NFL. Not because he played in the league for four years, with all the Inside the Huddle shows and a 24/7 network dedicated to the sport, fans know more about the league than ever. Rather, we can’t understand why he isn’t as rabid about the NFL as the rest of America.

“I am not a fan, it was work for me for so long, so I am too critical,” says Morgado, who has spent the past 14 years working as a financial adviser for Merrill Lynch.

This is not to say he doesn’t love the game. You can’t work as hard as he did making it to The League and not have a fire for the sport. He just doesn’t spend his Sundays on the couch yelling at the TV. When you earn something, it means more than just a cheap thrill on weekends.

His climb was a steep one from the start.

Growing up on an Ewa plantation, he was not the typical Punahou student. He worked in the cafeteria to help finance his education, and performed well enough on the field to get into Michigan State, where he spent a year before returning home to run the ball for the ‘Bows and butt heads with Coach Dick Tomey over efforts to recruit local players.

“I don’t know if I worked harder than anyone else – work was just part of my everyday living,” says Morgado. “It is how you become successful. You are not waiting around for someone to give it to you, but you work hard to do it yourself.”

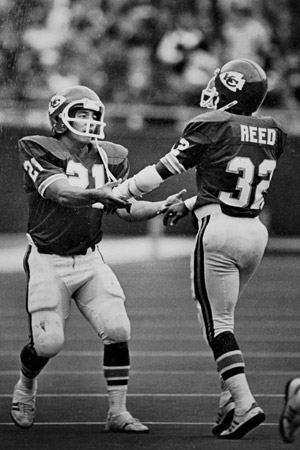

The same held true in the pros. He went undrafted out of college and beat the streets until he found a job hauling the rock for the Kansas City Chiefs.

“I would have gone anywhere, but Kansas City was where I could be afforded an opportunity,” says Morgado, who spent from 1977 through ’81 there while amassing 15 rushing TDs and just under a 1,000 yards for his career.

He spent some time away from the game, but returned this year to his alma mater to help coach the running backs in hopes that the lessons he learned fighting his way to the top filter down to the next generation.

“I like commitment and effort as a coach and a player,” says Morgado. “Those are really learned qualities and I hope it spills over into their personal lives.”

-C.P.

We all know the story: the young boy playing ball with his friends, pretending to make the game-winning catch, the fans in his mind roaring their approval. Most of us have had the fantasy, or at least heard the cliché a thousand times.

But not Blane Gaison. Even as the nephew of Herman Wedemeyer, he didn’t know he was allowed to have such aspirations.

“For me, a kid growing up in Kalihi, it wasn’t a dream I ever dreamed,” says Gaison, who spent four years playing defensive back for the Atlanta Falcons. “I never had any idea or intentions to play in the NFL.”

His lack of vision in no way impeded his talent, as he rose through the ranks to become the quarterback at Kamehameha, leading the Warriors to back-to-back state championships in 1974 and ’75.

True to his roots, he stayed home to play for his hometown ‘Bows, switching over to the defensive side of the ball to play cornerback, where he stayed except for one pivotal game against Colorado State. The team was down at halftime, and to mix it up the coach told Gaison to go change helmets, he was going in at quarterback.

“We came back out with like three run plays and two pass plays, and just did those and came back and won the game,” recalls Gaison with a laugh.

He got drafted by the Falcons in 1981, a team that featured backup quarterback June Jones and defensive coordinator Jerry Glanville, and suddenly the boy from the streets of Kalihi was playing against competition he had never even allowed himself to dream about.

“I remember listening to the national anthem and looking across the field and seeing Terry Bradshaw, Mean Joe Greene and Lynn Swann, and knowing I am going to play against them in a minute,” says Gaison. “They are history! What a real joyride, a wonderful journey.”

After his career, he returned home to work at Kamehameha Schools in the athletic department on the Kapalama campus, but on Jan. 1 moved to Maui to become the new athletic administrator at Maui KHS.

He loves his position, being able to help influence young people’s lives, much as his Uncle Herman helped to influence his own.

“I never got to see him play, but one of the things we always talked about was the passion,” says Gaison of Wedemeyer. “Whatever sport it is, you are playing to have the passion for the game and being the best. Give nothing less than your best.”

–C.P.

Charlie AneCharlie Ane was a big man, and not just in a physical sense. Ane’s success in football opened the door for generations to follow in the NFL. More important, his 40-year career as a high school football coach and athletic administrator provided opportunities for thousands of young student-athletes. Most important, in 1960, in the midst of a Pro Bowl career in which he helped lead the Detroit Lions to three division titles and two NFL Championships, he retired from professional football to bring his young family back to Hawaii.

“There were two reasons why my mom wanted to bring us home, to know our grandparents on both side and to go to Punahou,” says Ane’s daughter Malia. “They both were from Punahou and our family was from Punahou.”

Of course, players’ salary wasn’t the same in the 1950s.

“I don’t think he ever made more than $7,000,” says son Kale, the current Punahou football coach who followed his father to the NFL.

Even though the decision was the right one for his family, the move did separate him from a group of friends whose bond was lifelong. Which Malia got to see firsthand when she accompanied her parents to team reunions in Detroit.

“They just loved to play, they loved each other,” she says of the old Lions. “They took care of each other, they raised their kids with all of us. One funny thing I remember, whoever was the rookie on the team that year, was still the rookie. ‘You buy the drinks, you call for the taxi.’ Unbelievable. I saw the depth of that kind of friendship so many years later. Daddy’s roommate still called him Roomie.”

Carrying the Ane name in Hawaii athletics comes with a level of expectation. Never, however, from Charlie, who when the conversation turned to his own career, would quickly change the subject to his children or other kids he coached.

“He understood he was a big shot, so he tried to protect us,” Malia says. “But we always had to deal with it. That’s just the way it was. We couldn’t ignore it. You have to be proud of it, respect it but make your own path. Now as a parent you realize what a great message that is.”

If there was a downside to all his modesty, it was that his children never really knew how good their father was until they were much older.

“We never really knew how good he was because he never told us,” says Malia, who played volleyball at BYU.

The dream of playing in the NFL began at a tender age for Leo Goeas. Sitting next to his son on Sunday mornings, Larry Goeas would tell Leo he would one day be playing on TV. Whether the senior Goeas was peering into the future or it was the same message shared with each of his sons doesn’t matter. Leo made it, in great part on the advice and support of his father.

“Knowing how important it was to have one of his five boys play in the NFL, to have him see me play live, I automatically go back to third grade watching Sunday football with my dad. He’d say, ‘That’s going to be you one day, boy, you’re gonna be there playing.’ To actually live that out, even though it was kind of short-lived because my dad passed away days before my second training camp, that is my best memory of playing in the NFL.

Those are memories I will never forget.”

Those early chats while watching football weren’t the only time his father influenced an important decision.

Goeas chose to play for the University of Hawaii to be close to his father and because of the advice he got about his career after football.

“It came down to a conversation with my dad,” Goeas recalls. “He expressed to me the long-term benefit of those who decide to stay home and play here as it relates to opportunities post-college – job opportunities and such.”

Goes began his career with the San Diego Chargers in 1990 and finished eight years later as a member of the Baltimore Ravens.

A serious knee injury that required three operations to correct likely sapped him of the promise he showed as an All-Rookie left tackle. Still, he managed to bounce back quick enough to win the Ed Block Courage Award, an honor named for former Baltimore Colts trainer and given to a member of each NFL team who rebounds from major personal or physical challenges.

After 20 years away from Hawaii, Goeas returned in 2010. Perhaps again in reference to his father’s advice about the importance of building local connections, Leo and his older brother Larry created the Goeas Group, which provides financial and investment advice to institutional clients and individuals.

-S.M.