No Try Fool Me!

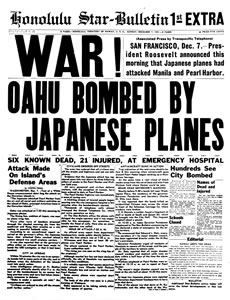

The Star-Bulletin rushed this front page “extra”off the press on Dec. 7

Editor’s note: This story is adapted from the forthcoming book Japanese Eyes American Heart, Volume II: Voices from the Home Front in World War II Hawaii.

By Gail Miyasaki

Seventy years ago, on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, at 7:55 a.m., Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in a surprise attack that shocked the United States and led to its entry into World War II. In Hawaii, the devastating attack cast suspicion on its Japanese residents, aliens and American citizens alike. In 1941, Hawaii’s Japanese were hard to miss, making up about 40 percent of the then territory’s population.

While much has been documented and justly celebrated about the valor and sacrifice of Hawaii’s 13,000 Nisei soldiers during World War II, less is known of the experiences of the vast majority of Japanese who lived through the bombing of Pearl Harbor by an enemy who looked like them. Two nisei, representing distinctly different experiences, share their personal recollections of Dec. 7, 1941, and wartime Hawaii as seen through local Japanese eyes:

U.S. planes burn out of control after being attacked on the ground; Honolulu Star-Advertiser photo

Jane Komeiji was a 16-year-old high school student in 1941, living in Aala with two younger siblings and their widowed immigrant mother, a successful businesswoman active with the Japanese Buddhist temple. Now 86, Komeiji is a retired teacher, co-author of Okage Sama De: The Japanese in Hawaii, 18851985 (1986, updated 2008) and involved with the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii’s Historical Gallery Committee.

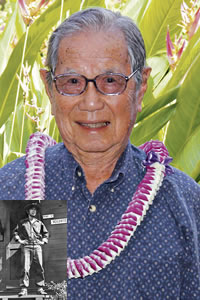

Ted Tsukiyama, in 1941 a 20-year-old University of Hawaii junior from Kaimuki, went on to volunteer for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the Military Intelligence Service in India and Burma. A Yale-educated attorney who marked a milestone 60 years as a lawyer in 2010 and is still an active arbitrator-mediator, Tsukiyama, now 90, is the historian for the Varsity Victory Volunteers, the 442nd and MIS in Hawaii.

Q: What was your experience on Dec. 7, 1941? What were your thoughts and feelings?

Ted Tsukiyama, then and now

Komeiji: Disbelief. This boy blurted out that Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor and we were at war. I told him, “No try fool me!” The dark smoke in the sky must be a house on fire. Sunday school was canceled because of the attack, so I phoned Mother that I would come home right away. But when one of the boys, wanting to show off his new driver’s license, offered a ride to see the Pearl Harbor fire, I jumped into his car with others. From Kalihi, we had a clear view of “Battleship Row” engulfed in a long, wide curtain of black smoke. I was disappointed. Where were the roaring flames?

The drive home was through eerily quiet, empty streets and sidewalks. At Aala Park, there were no Sunday evangelists at the corner, no games of sipa sipa (Filipino wicker ball kicking game), no baseball games and no crowds at the bus stops. I caught “hell” when I got home, two hours late. I had never seen Mother so angry.

Fearful of the enemy’s return by air or sea, we stayed indoors as we were told, listening to the radio about the curfew and blackout from dusk to dawn. We slept in our street clothes, with flashlights, jackets and shoes laid out ready to grab and go. I could not sleep: What if the enemy landed on Oahu? Where could we hide? What if my family got separated? These worries kept repeating in my thoughts.

Jane Komeiji, whose response to news of the attack is in the headline at the top of the page; contemporary photos by Gregory Yamamoto

Tsukiyama: I had gone to the university junior prom the night before, so I wanted to sleep late, but was awakened by a constant rumbling. I saw the sky black with smoke and heard the KGU radio announcer screaming, “Take cover! Get off the streets! We are being attacked by Japanese planes! This is the real McCoy!”

I was stunned: “This can’t be happening!” I felt total shock, then numb with disbelief and denial. When I realized that we were being attacked by Japan, I felt a twinge of shame for being Japanese, followed by anguish and despair from an awful foreboding of the suffering in store for us Japanese. I was consumed by anger and hatred for our attackers that would last for the rest of the war.

I was roused to action by the radio announcement for university ROTC members to immediately report to campus in uniform. Once there, I was handed a Springfield rifle and five bullets, even though I had never fired a gun before! By 10 a.m., this green bunch of college kids, most of us nisei, were sent to engage the Japanese paratroopers reported to have landed on St. Louis Heights. We were scared, sweating in the hot sun and swatting at mosquitoes till mid-afternoon for the enemy that never came.

Smoke from Battleship Row filled the skies

Around 4 p.m., our ROTC unit was converted into the Hawaii Territorial Guard (HTG) and sent to guard Iolani Palace, Hawaiian Electric, Board of Water Supply and the Iwilei industrial area. The night of Dec. 7 was the longest, darkest and wildest night I can recall with us bunking down in the old Armory. We were so afraid that the enemy would attack us again at any time.

Q: What was your greatest fear in the days after Pearl Harbor?

Tsukiyama: I can say without hesitation that I faced the worst moment of my life. In January 1942, after six weeks away from home with the HTG, we were awakened at 3 a.m. and told by our tearful commander that all HTG guards of Japanese ancestry were discharged. If a bomb had exploded in our midst, it couldn’t have been more devastating. I felt the bottom had dropped out of my life, abandoned and repudiated by my country. I had been brought up as an American; that blow was actually worse than “Pearl Harbor” to be told that you’re no longer trusted because you’ve got the same face as the enemy. When we parted, our officers, our fellow guardsmen, all of us cried.

Then Hung Wai Ching, secretary of the University YMCA and a key member of the Morale Section of the military governor’s office, challenged us. “If they don’t trust you with a gun, they might with a pick and shovel. Why not volunteer for a labor battalion?” We petitioned the military governor and 169 of us, mostly Nisei ROTC boys discharged from the HTG, left college to form the Varsity Victory Volunteers. For nearly a year, we did hard labor digging ammunition pits; repairing bridges; building roads, warehouses and huts. But we were the first all-nisei volunteer unit to go into service during World War II, even before the famed 100th Battalion. When the call came for the first all-Nisei combat team, almost all of us signed up for the 442nd.

Fighting a fire caused by the attack

Komeiji: We faced uncertainty, scary rumors of saboteurs, enemy invaders. When Japanese community leaders were taken into custody, I grew fearful that Mother would be taken away and even killed! Our store was regularly visited by the FBI. I was just a teenager what would happen to my siblings and me? We had no relatives on Oahu.

We adapted to martial law conditions like everyone else. As Japanese, we also had to discard our “Japaneseness:” Mementos, books, photos were burned, thrown or hidden away. As fears of an invasion faded, we went to dances and even being evacuated from our waterfront home, we kids looked forward to living with two other families like a big sleepover! None of my family members were ever called “Jap” to our faces. Our non-Japanese friends never shunned us or suspected we were disloyal. During the war, no act of sabotage or espionage was ever committed by Hawaii’s Japanese.

Mother fortunately was never interned. About 1,440 Japanese in Hawaii less than 1 percent of the local Japanese population were actually detained or interned. There was strong pressure to intern all of us like the West Coast Japanese. Younger generations today may not know that influential people, many of them haole community leaders, like Charles Hemenway, chairman of the UH Board of Regents, spoke up for us. They courageously and publicly expressed their confidence in Hawaii’s Japanese as loyal and trustworthy.

Q: What would you like to be remembered about Dec. 7?

The view from Pearl Harbor’s West Loch. Honolulu Star-Advertiser photos

Tsukiyama: I think of the words of Shigeo Yoshida, an unsung hero of the Emergency Service Committee, which was the military government’s liaison with the Japanese community. “How we get along during the war will determine how we get along when the war is over.”

Komeiji: The war accelerated many changes in Hawaii, especially making us a more democratic society. Japanese and non-Japanese alike worked together after the war to give us and future generations many opportunities we take for granted. We have a legacy of aloha in Hawaii that should be remembered as part of Dec. 7.