Chief Concerns

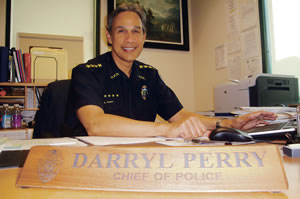

Did you know that in the past six months Kaua‘i Police Department officers have made more than 2,100 arrests? The man in charge is Chief Darryl Perry. He tells MidWeek about his earliest influences growing up on Kaua‘i and how the death of his son actually made him a better cop. Coco Zickos photo

KPD chief since 2007, Darryl Perry is well on the way to fixing a ‘fractured’ department that is kept busy fighting crime – making more than 2,100 arrests in the past six months

Kaua’i Police Department’s Chief Darryl Perry is responsible for keeping criminals off the streets. Like others who protect and serve, he is committed to ensuring public safety.

But it is his compassion and ability to regain the community’s trust in the local police department that makes him proud to wear his badge.

“I want to make sure that our community is free from the fear of crime and that they believe that what we are doing is right and they trust us,” says the Kaua’i native who was appointed chief in 2007.

He has since begun to rehabilitate the department after “tremendous controversy.”

“Internally the department was fractured,” he says of the KPD under Chief K.C. Lum’s tenure. “People didn’t trust one another, and this transferred into the community and the community didn’t have confidence.”

Chief Darryl Perry

Perry had originally applied for the position several years ago when Lum was selected.

“At first I was not going to apply,” says Perry regarding his decision to try for the position again. “They had their chance and I wasn’t going to put myself through that again. I personally thought the Police Commission’s decision at that time was wrong. K.C. was not qualified. What they did was put him in a position to fail because he wasn’t experienced enough, and I really felt sorry for him not knowing what he was getting into,” says Perry, his compassionate side finding its way into the conversation.

It is this softer side that is difficult to grasp when Perry first walks into a room – his stately appearance intimidating. But as soon as the former Kaua’i Interscholastic Federation basketball champ speaks of his difficult childhood and the tragic loss of his 26-year-old son Erikson Kapuni by suicide, his humanity shines through.

That empathy may have helped save Perry’s life one time when he was confronted by an outraged individual with a large meat cleaver – an incident he describes as the closest he has ever come to having to shoot someone.

“He had a domestic argument with his girlfriend, was distraught, and intoxicated,” says the formerly retired Honolulu Police Department major who can still recall the 1978 experience when he was serving as a Kaua’i police officer.

Chief Perry in his office at KPD headquarters

Originally from Lawai Valley – his grandparents first arrived in the islands from Spain in the 1800s – Perry spent a good portion of his life on Oahu, where he initially moved after attending Kalaheo Elementary School for only a year.

“My mom and dad got into a fight and the next thing I knew, the next day, we were in Honolulu,” he says. “We were running around in the pasture chasing cows and the next thing we knew we were living in tenement housing.”

But it was the first night he arrived that likely led the 1968 Kaua’i High School graduate toward his current destination. Overwhelmed by the city, Perry sneaked out of his new home and ventured into downtown’s Wool-worth’s department store to ride up and down the escalator because “I’d never seen anything like that before.”

When the store had to close its doors for the evening, Perry found himself completely lost and alone. A cab driver came to the rescue when he saw Perry wandering the streets in his pajamas crying. He radioed a police officer, who plucked Perry into the sidecar of his motorcycle and helped him find his way home.

With son Kapuni in 1980. Photo courtesy Darryl Perry

While the man in uniform became his knight in shining armor that evening, it was a chance encounter with a complete stranger that shaped his true compassion toward mankind.

“I still get emotional about this,” he says of a man who borrowed a hard-earned 10 cents from Perry while he was selling newspapers for lunch money, only to randomly return the payment months later tenfold.

“Back then, that was a lot of money,” says Perry, husband of Hawaii Health Systems human resources director Solette and the father of Erin and grandfather of 2-year-old Eli and 9-year-old Ellie.

“It had a huge impact,” he says. “It led me to believe in the kindness in people and trusting individuals. I have a tendency to be more tolerant and give individuals a second chance and even sometimes a third chance if they’re deserving and if they want to improve.”

But it was his son’s untimely death that had the largest impact in his life.

“The pain is always there, but the intensity lessens as time goes by,” he says of Kapuni who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia. “I’ve found that people who have lost children, we’re all in the same boat. It’s a different kind of pain in contrast to when you lose your mom or dad. When you lose your child, it’s something that’s almost impossible to describe to somebody who has never experienced that. Love your children while you can. Even if they give you a hard time, love them and hug them.”

sharing a light moment with capt. Kaleo Perez at headquarters. Coco Zickos photos

The sensitivity he now brings into the department because of this devastating experience wasn’t always there during his three decades of serving in the HPD.

“As a law enforcement officer before, I would do what needed to be done, but had no connection to those individuals,” says Perry, who was promoted to sergeant, lieutenant, captain and major while with HPD, even served four years as an officer with KPD during the 1970s. “Now there’s more of a connection.”

Instead of sending individuals with mental health problems into the criminal justice system, Perry is intent on seeking a diversionary method to help them.

“The criminal justice system, in some ways, has become the default mental health institution. We need to get treatment for these individuals.”

At home with wife Solette, daughter Erin, son-in-law Richard Loo and grandchild Ellie. Photo courtesy Darryl Perry

Though the job has gotten easier since his first day when he wasn’t even supplied with rudimentary items like pens or a stapler, the department is still a far cry from where he hopes it to be one day.

From adding four new beats to an island that currently only has 10, to recruiting additional police officers, the Vietnam Navy veteran has many aspirations.

Moreover, he hopes to help deflate the current crime rate, which has been on the rise.

A growing population, tough economy and rampant prescription and methamphetamine abuse is facilitating a growing epidemic of property crimes, domestic violence and traffic collisions and fatalities.

But the criminal justice system is also a factor in the crime surge.

“It’s this revolving door that creates these problems, and individuals who have drug issues that are not being treated,” says the bike-riding enthusiast who recently underwent a knee replacement.

More than 2,100 people were arrested in the last six months alone.

As a Kaua‘i native, the chief is sensitive to the community’s needs. Coco Zickos photos

“We’re the ones being blamed,” he says, “but the police do a marvelous job. I’m not being biased, just look at our statistics. We’ve been arresting these crooks and people who commit crimes over and over again.”

And as far as unsolved murders are concerned, Perry says, “hold onto your hat because cases are going to be solved … It takes time, and while I would like to let everybody know the progress we are making in these cases, I absolutely cannot because it would be irresponsible to the victim and the family members. And I know there are people just banging on our doors. But I can’t tell you what we’re doing because if I do, I might as well just give all the information to the person that we’re looking at. Mum’s the word until the case goes to court.”

So until more changes take shape within the department, he doesn’t plan to pass the torch or retire and fulfill his dream of traveling the Mainland in an RV, says Perry, who has seven brothers and sisters, including Kaua’i attorney Warren Perry.

“There is a higher cause here. We have an obligation to the public. We need to step it up and increase our service to the community; be more open and approachable.”