Fossils of Kauai

Paleoecologist David Burney

In Makauwahi cave, paleoecologist David Burney finds fossils from 10,000 years ago, as well as the earliest signs of humans on Kaua’i, and the impact they made on nature

Paleoecologist David Burney enters ‘Kaua’i’s real Lost World’ and discovers fossils from 10,000 years ago, as well as the earliest signs of humans on the island

An open-ceiling cave in Mahaulepu on Kaua’i’s south coastline, host to moonlit walks, dances of universal peace and curious hikers, has been the focus for the past eight years of deep investigation by paleoecologist David Burney.

A paleo-what?, you may wonder. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, paleoecology is “a branch of ecology that is concerned with the characteristics of ancient environments and with their relationships to ancient plants and animals.” In other words, Burney uses data from fossils to reconstruct the ecosystems of the long-ago past.

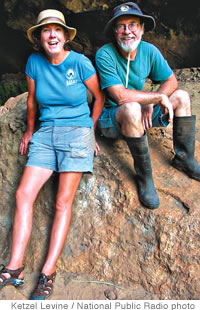

Along with his wife and collaborator of nearly 40 years, Lida Pigott Burney, and with help from hundreds of local volunteers, Burney has found 10,000-year-old buried treasure in the Makauwahi Cave – and this journey through time is the subject of his recently published book, Back to the Future in the Caves of Kaua`i, A Scientist’s Adventures in the Dark.

David Burney with wife and long-time collaborator Lida Pigott Burney on a 'dig' at Makauwahi cave

The treasure, of course, is not easily placed inside a pirate’s chest with the thought of reclamation. It’s been dug out of 30 feet of mud in some spots, and consists of, for example, fossils of a flightless Kaua’i goose, a turtle-jawed moanalo bird, two new extinct honeycreepers and a new species of bat, and seed pods and pollen from a plant so rare that only two exist in the wild.

It shows what once was, says Burney, and also what might be again. The cave is an enormous warehouse of information about the past that provides models for ecological and cultural projects throughout Kaua’i and elsewhere in the Islands.

“I think we’ve hit on some fairly simple and affordable strategies that are very satisfying not just to us, but to thousands who come to work in the cave or on the restoration side,” says Burney. “I think it’s a two-way nurturing process: We try to change our biota and in some ways save ourselves.

“It lifts the spirit, gives us lots of exercise, keeps us outdoors, forces us to work together and to make the best guess in going forward, drawing from the available science.”

Burney calls the project at Makauwahi Sinkhole “Kaua’i’s real ‘Lost World.'” Not only does the area contain a rich diary of life over the last several millennia, it also highlights cave mud records that begin about 1,000 years ago and show evidence of human activity, diet and the Hawaiian way of life before Captain Cook’s time.

European arrival is clearly signaled in these upper layers with the advent of abundant goat teeth and bits of iron, including nails from ships bent into hooks for fishing.

“In looking at what human environments were like in terms of fossil records, we gain appreciation for how much has been lost, just how thoroughly transformed a place like most of lowland Kaua’i is,” says Burney. “We seek necessary details to plan conservation better – and before it’s too late.”

Back to the Future in the Caves of Kauai

Burney, who by day is the director of conservation at the National Tropical Botanical Garden headquartered in Kalaheo, has led and participated in research projects all over the globe, including East Africa, Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands, North America, the West Indies and Hawaii. Prior to joining NTBG in 2004, he was a professor at Fordham University in New York City.

“I spent a couple of decades standing in front of college classes and telling them how to do conservation,” says Burney. “It was beginning to be a little hollow – I had a feeling I wanted to get back into doing conservation rather than talking about it.”

His research has focused on endangered species, pale-oenvironmental studies and causes of extinction, and has been featured on National Geographic Television, Discovery Channel, BBC Natural History, Hawaii Public Television, NOVA and National Public Radio.

Kaua’i tells a story that the rest of the planet can relate to, according to Burney.

“Everywhere in the world we have these huge conservation challenges,” he says. “In my opinion, we could be quite successful in most cases if we stop putting it off, burying efforts in paperwork, but instead turn out the whole community on a regular basis to do some good, solid work.”

Coming from humble, rural North Carolina roots, Burney had plenty of opportunity to explore his native area, and can recall clearly as a small child how he was fascinated by natural history and Native Americans. Like ohana here, he grew up with extended family and revered his kupuna. He has fond memories of time spent on the farm of two great-grandparents on one side of the family and a grandfather with half Native American blood on the other.

With interests he classifies as “nerdy” – bird watching, for example – Burney seemed destined for a career involving nature, and became a park ranger, working up to a regional naturalist position.

The next leap was quantum – and life-changing. Armed with a Rotary Foundation International Fellowship to be pursued in the country of his choice, Burney flew to Nairobi, Kenya, to earn a master of science degree in conservation biology.

“That’s when my world suddenly expanded from local to global,” he says. “I saw just how much there was at stake in the biodiversity crisis.

“It made me think in deeper time frames … It set me in the direction of thinking about paleoecology, the study of past environments.”

Pursuing a Ph.D. at Duke University, Burney met Daniel Livingstone, a cousin of the African explorer David Livingstone. Daniel was a specialist in tropical paleoecology. Burney’s later studies on Madagascar hooked him into studying islands, and in the three decades he’s conducted research there, he met scientists who worked here, too, which ultimately led him to Kaua’i.

“I’m extremely interested in the changes over time on whole ecosystems at a global scale,” he says. “I’m interested in how humans impact environments, how people affect nature.

“One great thing about Kaua’i is that it’s small enough that we can wrap our minds around it. The world is such a huge challenge, it gives a sense of hopelessness – people need hope in order to feel conservation efforts are even worth trying.”

David Burney

Burney points to the strides made at Makauwahi Cave, in particular to 17 surrounding acres leased from Grove Farm Company and outplanted with native plants started from seed collected by the field botanists of the National Tropical Botanical Garden. Now many of the native species reintroduced to the site are reproducing on their own at Makauwahi Cave Reserve, and surplus seedlings removed carefully in the thinning process are used for other restoration projects.

“I think there’s a lot of hope here,” says Burney. “Some people say too many things have changed, that it’s a kind of a Humpty Dumpty thing. In this pessimistic view, the ecology of Hawaii and other places is broken and can’t be fixed. If we take that attitude, we won’t even try to fix the problems, that’s for sure.”

Burney, who’s seen at least two dozen native plant species on Kaua’i decline to extinction or near-extinction over the past six years he’s been working at NTBG, remains indefatigable in his efforts.

“I’m the sort that really doesn’t give up on a species until the last individual is gone,” he says.

“I know when I do everything I can to help the natural world cope with everything all we humans throw at it that it is very satisfying, and that feeling is enough for me.”

On July 15 at 6:30 p.m. at the Koloa Neighborhood Center, the Koloa

Community Association and Malama Mahaulepu will host a presentation by Burney on the discoveries at Makauwahi Cave at Mahaulepu. In addition to the presentation, the evening includes a reception with book-signing, pupu and dessert. Call 651-1332 or go to koloacommunityassociation.com or malamamahaulepu.org.