Justice on the Horizon

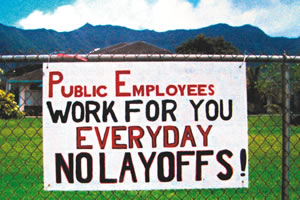

One of many signs Catania created last year.

Photo courtesy Raymond Catania

Whether it’s native Hawaiian rights, the divide between rich and poor, Furlough Fridays or world peace, Raymond Catania refuses to give up the good fight to achieve social justice for all

Unlike many of his generation, Raymond Catania never gave up the fight for peace and social justice

There is a global epidemic between the haves and the have-nots, says Raymond Catania of Kaua’i Alliance for Peace and Social Justice.

“The world’s resources should be shared with everyone,” he says. “If we did, there would be no war.”

Although the problem is global, Catania says he is driven to act locally, and is one of the few people brave enough to take to the streets adorned with signage not only in protest of war, but as an active advocate for environmental issues, Hawaiian rights and social equality.

In fact, the Department of Human Services Social Services assistant was hard to miss last year when he protested the state’s proposed furloughs and layoffs along Kuhio Highway in Kapa’a.

“We’re just working people trying to survive to support our families and pay our bills, and at the same time perform a pretty good public service in helping disadvantaged, abused children – trying to make an environment safe for all children,” he says. “The rebellion on Kaua’i started on the bottom. We didn’t have the union officials telling us that we should go out and demonstrate, it was the workers from below who wanted to do it. It was a real spontaneous reaction.”

It was Catania who initiated the movement on Kaua’i that essentially helped preserve many jobs for his co-workers, says Kaua’i Alliance for Peace and Social Justice member Kip Goodwin.

“It was Ray, standing out in front of union management, who organized and empowered his fellow workers and others to strongly support the passage of Senate Bill 2650 (which prevented the reorganization of several Neighbor Island social service offices).

Raymond Catania got a taste of injustice at an early age.

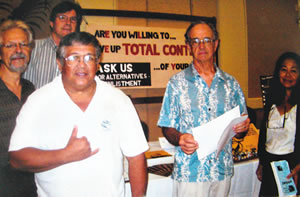

Coco Zickos photo

“We think his behind-the-scenes activism over the years makes him one of the most influential people on the Island.”

Though Catania helped propel the action, he says it was his co-workers who really ignited the flame.

“The women had so much fire because they were mostly mothers and have to put food on the table, and nobody was going to take their livelihood away and put their kids out into the street,” he says. “So they had so much passion in them. In a way, I followed them, I took the lead from them.”

While layoffs and furloughs did occur, the real victory was that the women felt empowered.

“To me, that is a victory in and of itself,” he says, “because it sets the groundwork for people standing up for themselves in the future.”

Impromptu, straightforward action that comes from the bottom is how movements are built, Catania says. And he should know, as he has supported social justice activism since he was a sophomore in college on Oahu, when he collected and burned some 200 draft cards in protest of the Vietnam War.

“I had friends going to Vietnam and not coming back,” he says. “I started questioning what was really going on.”

But it was during his teenage years that Catania began considering championing equal rights for citizens, including native Hawaiians.

Born and raised on Oahu, Catania witnessed it turn into a concrete jungle. During his childhood, what were once farms and fishponds in the Damon Tract area where his family lived modestly became Honolulu International Airport.

“Whenever I go there it hurts because I remember the old days,” he says.

His family was eventually evicted and he moved to Waianae, where he had a similar experience as a teenager. The young surfer was dismayed to discover one day that his regular North Shore hangout had been barricaded to prevent public access.

“I tried to go surfing and there was a fence in my way,” he says. “A guy came out of the house and said, ‘Hey, man, get out of here, you’re trespassing.'”

Catania with fellow activist Kyle Kajihiro.

Photoa courtesy Raymond Catania

That was what Catania calls his first run-in with gated communities.

By the early 1970s, he helped organize a group of college students to occupy Kalama Valley on the East side of Oahu for more than a month to stop the eviction of Hawaiians and farmers in the area.

Even though he was among the 32 protesters arrested, Catania says the action assisted in educating many people in Hawaii about the history and, he says, “theft of the lands and overthrow of the government.”

Since then, Catania has played an active role in teaching others about the plight of the Hawaiian people and their right to self-determination.

Though he is not of native ancestry himself, Catania, who with wife Brenelie, a Marriott employee and Garden Isle Healthcare nurse’s aide, has two teenage girls, Dulce Amor and Dolly Moani, says he doesn’t mind explaining to nonHawaiians why we should support them.

Also a member of Mana Oha – a group that works with native Hawaiians to enlighten the community about their history through movies and lectures –

Catania supports sovereignty and independence.

“This is their home and they have suffered the most,” he says.

“Their culture has been used and abused by a lot of people to make money. And they’re not the ones really benefiting. They are at the bottom economically.”

The drive for profit is hurting people around the world, he says. Breaking down the war economy would help take care of those at the bottom of society’s monetary rung.

Not only does he believe that military lands should be returned to native Hawaiians, but without the government’s financial obligation to war, working class economic hardships could be lessened.

(from left) Fred Dente, Raymond Catania, Kip Goodwin and Joan Heller at an event encouraging people to consider alternatives to joining the military

“Instead of spending money on things like missiles and bombs, and two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the government should be spending money bailing out the states,” he says. “That’s our money and that’s where it should come from. It’s like a big elephant in the room that nobody’s talking about.

“In terms of solving the economic crisis, it can be solved if they give the money back to the working people, the people creating all the wealth anyway.”

But it’s really up to the individual to stand up for these rights. Catania also spends his time defending sacred sites on-island and halting development on ancient burial grounds, because if people don’t speak up, they’ll continue to be taken advantage of.

“I don’t have all the answers, but I know something: I’m going to continue to be involved in fighting against any kind of injustice,” he says.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There are no comments

Add yours