Leading By Example

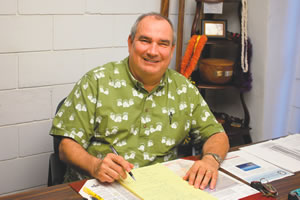

County Council chairman Jay Furfaro's daily goal is 'just to be a good steward ... The vision that I have for Kaua'i is one that really perpetuates that Hawaiian sense of place and embraces a Hawaiian series of values, especially as it relates to the way business is done - with mutual respect and aloha. Amanda C. Gregg photo'

Whether working in hotels or politics, Jay Furfaro feels an obligation to preserve and perpetuate Hawaiian culture and values

He’s more than just the moderator for the island’s district leaders. Waianae boy, Project Punahele author and founding Leadership Kaua’i executive director Jay Furfaro is a treasure trove of Hawaiian culture who is toeing the line for a more efficient, fiscally and historically responsible county that is true to its roots and traditions.

Though many know him for his County Council budget-speak of late (he seems to often use words such as “tax rate,” “reserve” and “earmark” on his tongue during those public Wednesday meetings) the reason County Council chairman Furfaro got into public service speaks to his idealism as well as his down-to-earthiness: Lead well and others will follow.

Or, as he puts it, “just be a good steward.”

It makes sense that someone with such lofty and concise views would spearhead projects that put those ideas into practice, such as Project Punahele, a historical overview of Princeville at Hanalei, and Leadership Kaua’i, a mentoring and training program to ensure the next generation of leaders has the tools necessary to carry out a cohesive vision for the Island and its people.

Calling it part of his (native Hawaiian activist) George Kanahele mindset, even during his 37 years in the hotel industry, ranging from the Hanalei Plantation and Coco Palms to Westin and Outrigger resorts, Furfaro knew there was an obligation for those in that line of work to help preserve Hawaiian culture.

“It’s important to recognize the stewardship associated with the resort business,” he says. “They should represent a true sense of place.”

Chairman Jay Furfaro in his office. Amanda C. Gregg photo

Stewardship seems to be a recurring theme in Furfaro’s life, as is cultural preservation. Taking it upon himself to teach Hawaiian culture to the visitor industry, he created Project Punahele, a compelling and rich historical document that tells the story of the North Shore dating back to 1736. Depicting old Hawaii where every passerby, whether an acquaintance or a total stranger, was greeted and offered food, the presentation covers everything from who Princeville streets are named after, to the birth story of kalo and the Hawaiian music inspired by the old vaqueros, or paniolo.

To be sure, it’s a document that exemplifies Furfaro’s passion for history and Hawaiian culture.

“The vision that I have for Kaua’i is one that really perpetuates that Hawaiian sense of place and embraces a Hawaiian series of values, especially as it relates to the way business is done – with mutual respect and aloha,” he says.

Furfaro, whose mother’s half sister’s great-grandmother was a Johnson/Pali family member and teacher at Waioli, says he was visiting the North Shore to surf one summer when he met his wife of 37 years, Ema Gomez.

The couple has since become grandparents thanks to their daughters Nicole, Jennifer and Marissa, all three of whom are Kamehameha Schools and University of Hawaii graduates.

“I met my wife when I came over for surfing in Hanalei in the mid-60s,” he says. “And then subsequently when I finished hotel school and got my first assignment, I met my wife again. She was a member of the Barry Yap Hula Halau and she danced at the hotel.”

A keeper of his wife’s family records, Furfaro says her side dates back to the original Spanish cowboys at Princeville Ranch. Referencing how the word “paniolo” for vaquero or cowboy is a truncated version of hispanos, the word that was used to describe the Spanish cowboys of the time, he smiles at yet another chance to speak about what he loves: culture, language and history.

And it’s with that passion that the civic leader became the founding executive director of Leadership Kaua’i in 2001.

The program came to fruition following a visit from “futurist” and guest speaker Ed Barlow Jr. to a Kaua’i Chamber of Commerce meeting.

“He talked about things happening in different communities across the nation,” Furfaro says. “Communities weren’t just investing in capital improvements and those kinds of tangible areas, but planning how to strategically grow leaders.”

Barlow’s points made a handful of chamber members – who knew Furfaro was close to retiring – propose a joint venture in launching Leadership Kaua’i. Of course, the fact that Furfaro had previously served as the president and treasurer of the Hawaii Hotel Association, finance chairman of Kaua’i Economic Opportunity, director of the Salvation Army, president of Kaua’i Historical Society and had been such an integral part of Kaua’i’s Habitat for Humanity – which was all about providing opportunity for families – made him an ideal match for the project.

They created a nine-month-long training program template based on Hawaiian values and community resources for developing future leaders.

“Those who wanted to be part of the program had to demonstrate in their application that they were examples of being good stewards,” Furfaro says.

Those familiar with the Leadership Kaua’i program know it has since become synonymous with creating future leaders – Mayor Bernard P. Carvalho Jr. is among its alumni. But the program also bears one of Furfaro’s signature stamps: a cultural history component.

Believing that every Hawaiian word was created as such for a reason, Furfaro believes keeping culture in place begins with preserving the Hawaiian language and being aware of its etymology.

His eyes light up when he describes the history of Hawaiian place names – even surf breaks – and he says it’s extremely important to hear from previous generations to keep local culture alive.

Furfaro is equally comfortable talking budgets, leadership or surfing. Amanda C. Gregg photo

Having spent much of his life surfing (he traveled to Tahiti as an exchange student in 1963, but admits he surfed more than studied), Furfaro says that even local surf break names have morphed away from their Hawaiian roots.

“‘The Bowl’ and ‘The Bay’is a surf spot that’s really Manulau, named after the reef that’s under the channel there,” he says. Offering yet another example of place-name evolution, he says the channel leading to what people refer to as the rice fields next to Hanalei plantation is really ka mo’o mai kai fishpond, meaning the “benevolent lizard.”

“Even as you look out at places like kalihi kai versus kalihi wai, it has a historic name referencing Emmasville, that is an anointed name, versus Princeville, where a lot of people don’t realize it’s named after the young prince of Hawaii, Albert Edward Kauikeaouli lei o Papa a Kamehameha, son of Queen Emma and King Kamehameha IV.

“People are kama’aina to a certain area,” he adds, noting that identical place names are common throughout the Hawaiian archipelago. “We have na pali, the cliffs; Hale lea,joyful house; Ko’olau, which references the windward side; Puna, which subsequently has the name kawaihau, which references the ‘hard water’or ‘ice,’like the ice from Mauna Kea that used to be shipped to Kealia to enjoy okole hau, or Hawaiian whiskey,” he says.

Using the popular spot “Queen’s Bath” as a place name example, Furfaro offers another point of reference for the saltwater pool that has become infamous for its rogue waves.

“It has a Hawaiian name, Waimaumau,” he says. “This evolution of various place names happens because the historic value in the Hawaiian place name isn’t respected.”

Beyond keeping culture alive and well, Furfaro also is all about helping local families sustain their livelihood. The creator of the Kuleana bill, which kept Hawaiian family lands in Hawaiian hands, as a councilmember he is most proud of having introduced the 2 percent tax cap for primary residents.

“It gives people an opportunity in these very challenging economic times, where government subdivisions are looking to live within the operating costs of government, and at the same time make sure there’s a fair and predictable tax rate for our primary residents,” he says. “The idea is, though you still have to pay, at least you can budget for it. I’m really proud of that.”

He is looking to further help the local economy by getting the papaya treatment facility up and running again, but more than, that he’s looking to create a reserve policy to help safeguard Kaua’i coffers so that, in the event of an emergency, funds will be available.

“I have strongly requested the administration to come to the council with a reserve policy that would earmark 20 percent of our budget as a fund that we could reach to in the event of emergency,” he says. “Currently we have a surplus, but we’re using the wrong term. It should be a ‘reserve,’not a ‘surplus,’and the reserve should have a cap each year.”

If we have to replenish the reserve, then what isn’t committed to capital projects and other costs might help manage future tax growth.

But above all, Furfaro, a graduate of Waianae Elementary and former Searider football player who studied the hotel and restaurant business at Kapiolani Community College, says keeping people educated on local history and Hawaiian traditions needs to remain a priority.

“I see a need to make sure we reinvest our time in Hawaiian values,” he says. “It is our task to perpetuate it and keep it alive.”