Lucky Luke

The day he nearly died in the Kaiwi Channel is really the day his life began, says Luke Evslin. And he's now living it to the fullest while also living off the grid and running a company with two old school pals

The day his life nearly ended in the Kaiwi Channel is the day his life really began, says Luke Evslin, and he’s living it to the fullest

It’s a chickenskin moment when paddling phenomenon Luke Evslin talks about what could have been the end of his life.

Yet somehow what he’s simultaneously describing is his life’s beginning.

“It’s kind of corny, but I remember thinking, ‘I’m going to die,'” he says. “But I wasn’t scared about death, I just had this feeling of love for everybody around me and was sad to be leaving that. I’m not that kind of person at all, but I just felt like, ‘I don’t want to leave this behind.’ I just felt waves and waves of love.”

Evslin, a 27-year-old Kaua’i native, sustained lifethreatening injuries when the propeller from an escort boat sliced into his back during a water change in the 2010 Moloka’i Hoe, an annual event known as the season-capping mother lode of six-man outrigger canoe races.

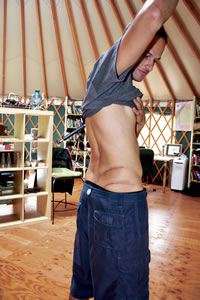

Luke Evslin, now a vegetarian, and known as a ‘gentle soul’ by friends, with his duck at his home in Wailua Homesteads Amanda C. Gregg photo

Though it’s early in the season, Evslin has created quite the buzz on-island with the progress he’s made with Pu’uwai paddlers, having taken them from a group that started with six people to a team burgeoning at the seams.

“I think now we have around 70,” Evslin says. “We take out nine canoes at most practices.”

Pu’uwai paddlers Brandon and Sonya Raines say Evslin has brought a new positive energy to the club.

“He’s just such an old soul for his age, and so inspirational,” says Brandon Raines, who paddled for the club when Evslin arrived as coach.

During the next six months, Evslin will be training crews for the course on which he was injured, the 40-plus-mile Na Wahine O Ke Kai and Moloka’i Hoe across the Ka’iwi Channel.

“Our entire goal is Moloka’i, and hopefully every crew will go,” Evslin says.

The men’s Moloka’i race, running since 1952, for decades has begun with hundreds of escort boats and canoes incredibly close to each other out of the gate, especially until the first water change, in which paddlers jump out of escort boats and tread water waiting for canoes to approach.Paddlers then climb into the canoes on the left side to relieve paddlers who jump out on the right. If all goes well, the canoe keeps moving forward as paddlers unzip the canvas and jump out, and replacement paddlers climb in, zip up and start stroking without missing a beat.

Since Evslin’s accident, the canoe association has lengthened the first change to be farther out, so that canoes and escort boats have roughly 15 more minutes to spread out into the channel.

But there’s still no law on the books regulating the licensure of boats or the requirement of propeller guards for these long-distance races. Evslin says encouraging legislators and insurance companies to offer incentives to boat owners who use propeller guards could help save lives. “My accident was totally preventable,” he says. Canoe clubs also could fundraise to purchase propeller guards, which range in price from $200 to $500, for the escort boats, he adds.

It was during the first water change that Evslin, paddling at the time for Kailua Canoe Club, jumped out of the escort boat to replace the stroker in seat No. 1. He never made it into the canoe, and neither did the other relief paddlers who were treading water alongside him, Donovan Leandro and Makana Denton.

Evslin’s sewn-up wounds after three surgeons simultaneously operated on him Photo courtesy Luke Evslin

Evslin was left with a series of 5-inch-plus-wide lateral slices to his torso, which left his spine exposed and drained him of enough blood in the water for crew members to think he had been attacked by a shark.

Remembering the moment in the water when he was screaming out for help, Evslin, without regard to the trauma he endured, recounts the incident with empathy for what his crew must have been going through.

“They had to keep paddling that whole race not only without an escort boat, but wondering, ‘Is Luke alive or dead?'” he says.

It’s that kind of selfless, non-victimized attitude that seems to define Evslin more than being a survivor, according to his mother Micki, who was on the Mainland taking care of her 95-yearold father when she got the phone call that her son had been airlifted to Maui Memorial Medical Center.

“He insisted I not come back because he was in the hospital, and he said, ‘There’s nothing you can do,'” she says. “He said, ‘Come home when I’m out of the hospital and be with Grandpa another week.”

It was likely his strength of mind that got him through what was arguably as traumatizing as the initial injury, the seemingly eternal transport from the accident site to the surgery table, all of which he endured without pain medication.

From having to initially climb the ladder back up and into the escort boat with an exposed spine, to overhearing that because of a jurisdiction dispute the Coast Guard might not airlift him out, and a paramedic saying to another, “He’s not going to make it if the helicopter doesn’t come,” it was a long trek to the hospital, to put it mildly.Pu’uwai Canoe Club president Brian Curll, who has worked to get propeller guards required by his canoe club for water change races like Kaua’i’s Na Pali Challenge, says there aren’t enough licensed escort boats here. Curll says it’s a mutual understanding that the Coast Guard stays out of longdistance events, as racing canoe is considered a cultural practice.

“Part of why the Coast Guard didn’t activate the helicopter is because it has to pretend the race doesn’t exist,” he says, adding that had Evslin’s injury occurred in the middle of the channel, he would have died.

Getting Evslin back to land before being airlifted included an additional bodysmacking 45-minute boat ride to shore as paramedics sat on him to prevent further blood loss, (two days later he had regained only 40 percent of his blood) all the while not explaining to him the extent of his injuries.

“I would hear a gasp every time someone saw me and I just wanted to know how bad it was,” he says. In addition, Evslin kept having to witness new people reacting to his story each time he was transferred.

“I would tell them, ‘I got hit by a boat,'” he says. “One nurse kept poking me, asking me, ‘Does this hurt? What about here?'” Finally, a whopping three hours after the accident, he finally arrived in the operating room. “I asked the urologist if I could borrow his phone to call (fiancée) Sokchea,” he says, adding he was relieved to have made it this far.

Luke Evslin showing off his garden at his home in Wailua Homesteads, which includes fresh basil Amanda C. Gregg photo

Strangely, as he puts it, he was lucky. Three propeller-related fatalities have occurred in the state since his accident.

In Evslin’s case, the first of the five cuts actually pushed him away from the boat, and the only muscle to be severed was his gluteus muscle, which spared his vital organs. The blade that crossed his spine broke the bone away, but didn’t sever the cord. Redefining the term “lucky break,” Evslin says even the blade that broke his pelvis bone sliced it “clean,” rather than the manner in which a pelvis usually breaks: in two. “It snapped it like a chicken bone, which was really good,” he says.

“Literally everything that happened from the moment of the first hit that moved me enough to keep my spine further away, to the Coast Guard helicopter not coming, which would have been worse because I would have had to get back in water and hoisted up, I was lucky,” he says.

The accident also changed his perspective, something else for which he’s grateful.

Evslin, now a vegetarian who rides a bicycle and lives off the grid in a yurt with his wife, has committed to a completely sustainable lifestyle.

“He was always sensitive, but now it’s like his heart breaks for the earth,” Micki says. “He doesn’t want to hurt anything. In healing himself he wants to heal everything.”

Returning to the Garden Island to heal was a blessing. He returned to be with his mother and father, Dr. Lee Evslin. Soon after his return he married Sokchea in two ceremonies, first in a Cambodian wedding with her family in California and second at his home in Wailua Homesteads with brothers Nathaniel, Noah and sister Tanya among 200 guests.“It all worked out for the best,” he says. “One moment you’re in a boat thinking, ‘I’m about to do a race,’ then it’s, ‘I’m going to die.’ All of a sudden your world goes upside down and you understand mortality and how quickly things change. It’s a slippery slope. You start seeing everything.”

As for whether he will compete in the 2012 longdistance Moloka’i race alongside the team he’s prepping to go, Evslin offers a humble answer. “If I make a crew,” he says.

Regardless, “My main passion is Kaua’i. I love this island and everything about it. But it is really frustrating to see the direction we’re heading. I would like to work toward sustainability, whatever that means.”

And he continues to run the business side of Kamanu Composites from home, the business he owns with school classmates Kelly Foster and Keizon Gates.