Serving the ‘Aina

Whether it's cleaning up the overgrown Coco Palms site or promoting Polynesian values through his nonprofit Children of the Land, Phil Villatora says it's all about serving and preserving the land

Whether it’s cleaning up the old Coco Palms site or teaching folks to play the traditional nose flute through his nonprofit Children of the Land, it’s all about serving the ‘aina for Phil Villatora

Gnarled branches and mangled weeds are thinning out at the dilapidated Coco Palms, thanks to Phil Villatora.

The Kaua’i native has been voluntarily clearing out some of the debris that has plagued the defunct hotel since Hurricane ‘Iniki pillaged the island nearly 20 years ago.

Though it’s a job the current owner has less than a year to complete, Villatora couldn’t stand to watch the beloved site continue in its current condition and decided to do something about it.

“Let your actions speak,” he says. Villatora has been doing as much as he can to physically maintain the property for approximately three months, after he was given permission by the owner.

“I’m honored,” he says. “I’m serving the land.”Though the ultimate task will require more labor than one man can do, transforming the area into a Polynesian/Hawaiian cultural center is what Villatora would eventually like to see happen.

It’s something he has already accomplished elsewhere.

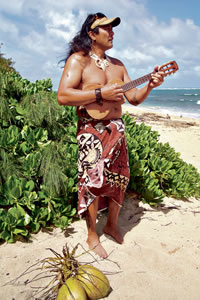

The 1983 Kaua’i High School graduate helped found the nonprofit Children of the Land (Na Keiki ‘O Ka ‘Aina) approximately two years ago to perpetuate the arts of Polynesia and ancient Hawai’i. The organization offers classes, including Tahitian drumming and hula, to people of all ages, kama’aina and visitors alike.

Children of the Land, which is located at Kaua’i Village Shopping Center, has amazing artists who share their talents on a regular basis, says Villatora, who is one of the many instructors.

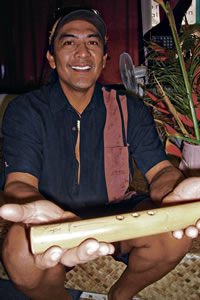

One talent Villatora likes to share with others is the creation of nose flutes – an instrument that he says was used for healing purposes in Polynesia.

“You get to feel versus think,” he says about playing the instrument.

The class is offered once a month and anyone can participate. During the all-day class, students learn the basics of how to play and even make their own flutes from bamboo they harvested on a field trip.“They harvest their own and connect with it,” says Villatora, who also teaches Tahitian drumming three days a week.

Folks also can be entertained by classes in Samoan fire knife dancing and poi ball spinning, as participants perform outside on the stage adjacent to the building.

As many as 100 people are estimated to walk through the center’s doors each day, but making it come to life wasn’t easy at first. It took a lot of effort to transform the space into a community hub.

“It took a lot of vacuums and a lot of hard work.” says Villatora. “The volunteers have been amazing, over the top.”

One such volunteer who was particularly helpful is Ray Harris. Harris appreciates the knowledge Villatora is sharing with the community, especially children. His granddaughter Mattie attended Children of the Land’s six-week summer camp with Villatora.

“They have a great time, and she just loved it,” says Harris. Mattie returned home to San Diego and won a talent contest performing poi ball dancing she learned during camp.Keiki also learn to husk coconuts, dance hula and host a luau. In addition, they visit many places across the island and learn what the island naturally has to offer.

“Nature is our teacher,” says Villatora. “The arts are beautiful in what they supply us, and most of it comes from nature.”

He has always felt that way growing up on the island and immersed in Polynesian culture. Though he is not of Hawaiian descent, his grandparents were the first generation to arrive on-island during the plantation era and taught their children how to live off the land.

“We never really needed much,” he says about his six brothers and sisters who grew up raising animals and maintaining gardens.

“Anything we did, we always asked permission – from using rocks or wood to burn or to even swimming in the ocean,” explains Villatora, who was responsible for collecting coconuts for his family, which included his mother Leonora. “It was the protocol on how to give back to the land first. We were always aware of giving to Kaua’i, because the land had always fed us.”

His late father Vick used to teach his children to always put the first fish they caught back into the ocean. Villatora continues to uphold his father’s many teachings.“For what he has done, he is still here,” he says.

Staying close to the land is the message Villatora still carries into the teachings at the Children of the Land. But a Polynesian cultural center wasn’t always his passion. After high school, Villatora moved to California, where he became a security guard for the San Francisco 49ers.

“That was beautiful,” he says about the games at Candlestick Park. “You talk about energy, wow! The mass amount of people – that’s the entire (population of) Kaua’i in one stadium.”

Villatora was brought up playing sports, including racquetball and volleyball.

“Sports was my main thing,” he says, adding that it still is at times. “If I get stuck near a TV, it’s the sports station.”

His stay on the Mainland didn’t last long.

“I would meet people out there, send them to Kaua’i and they would bring back photos,” he says. “It made me homesick. It made me question what I was doing there.”

When he returned to the island, all Villatora wanted to do was share Kaua’i with visitors. He worked for various tour companies.Eventually, Villatora, who now lives in Kapa’a, found other ways to share the island with visitors. His brother Jon, who had a dancing gig at the Lawai Beach Resort, introduced him to fire dancing and drumming. It helped inspire Villatora to create instruments of his own. By the 1990s, he was taking his instruments up to Wailua Falls where he would play them for visitors every day.

“I just went out there knowing that it felt good from my na’au – which is your gut feeling,” says Villatora, who would also fill his truck with fruits and vegetables to share.

He soon landed a job at Kaua’i Hilton, where during its luau he performed, with children ages 4 to 15, the story of a princess dreaming of a voyage to the South Pacific.

Former Kaua’i Hilton employee Sue Kanoho remembers Villatora there.

“I’ve watched Phil grow from a focus on drumming to now working to highlight others, along with their cultural craft/talents, through Children of the Land,” says Kanoho, Kaua’i Visitors Bureau executive director.

Now, Villatora performs the same story at the Luau Kalamaku at Kilohana, where he has been drumming three nights a week since 2008.But it’s at Children of the Land where Villatora invests most of his time and energy these days. And while that center is new, he actually created a cultural center on his late father’s property many years ago called Vick’s Tropical Garden of Eden.

“It was the full circle of sustainability,” says Villatora, father of Noenoe (18), Kyran Brooke (17), Xena Phil (15), Chaning Philip (12) and Aza (12), about the property. “Everything you needed as a village or community center, it was there.”

He takes the same approach at Children of the Land.

“Phil is a very compassionate and a very passionate person at the same time,” says Children of the Land president Evan Meek. “He’s not a follower, he’s definitely a leader.”

When Villatora isn’t spending time with his fiancée Jodi Martin, who works in the X-ray department at Mahelona Hospital, he is dedicating as much effort as he can toward serving the ‘aina and perpetuating the host culture through his organization and volunteer efforts.

“I’m giving back to Kaua’i what it has given to me.”