The Tube Dudes

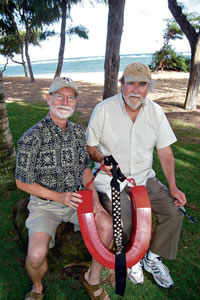

Branch Lotspeich and John Gillen along with fellow Rotarians have placed nearly 200 rescue tubes around Kaua'i, the drowning capital of Hawaii, and so far they're credited with helping save at least 40 lives

At least 40 lives have been saved thanks to Branch Lotspeich and John Gillen and their rescue tubes

Panic courses through your body when you’re caught in a riptide.

As Branch Lotspeich knows very well.

A former lifeguard, he experienced a “very real moment” of distress while trying to swim back to shore at Hanalei Bay several years ago.

“All of a sudden, it was that sense of ‘I could be in real serious trouble right now,'” he says. “And that’s what happens to people.”

Which ultimately led to him becoming executive director of Kaua’i Rescue Tube Foundation.

Flotation devices created by the foundation now serve as a link between life and death for swimmers struggling against the power and whims of the ocean.

The nonprofit has been responsible for installing nearly 200 rescue tube stations that dot beaches around the island, particularly those where lifeguards are not stationed.More than 40 saves have been reported using these emergency instruments, and nearly 20 drownings have been prevented since the foundation’s inception approximately two years ago.

The rescue tubes are attached to poles buried deep in the sand at the vegetation line. At the top of every pole is an easy-to-spot yellow or red flag. Each tube can be grabbed quickly and contains simple instructions.

“The graphics are such that, even if you don’t read English, if you’re a visitor without English skills you can still kind of figure it out,” says Lotspeich.

Bringing the flotation tool to a swimmer in distress allows them to have something to hang on to while they wait to be rescued.

Branch Lotspeich works on the assembly of a pole that will soon house a rescue tube along one of Kaua‘i’s beaches and could one day save a distressed swimmer's life. Coco Zickos photos

says Kaua’i Rescue Tube Foundation’s John Gillen. “You’re not rescuing someone who’s drowning you’re rescuing someone who’s in distress and will drown if you don’t help them.”

“For safety reasons, we also make it clear: If you can’t swim, don’t use this device, don’t go in the water,” adds Lotspeich. “We’re not asking anyone to go into harm’s way unless they feel like they know what they’re doing.”

And the first thing to do, always, is call 911.

“The idea is your own personal safety first and then, secondly, you have a personal floatation device to rescue the person in distress,” says Lotspeich.

The most recent documented save with a rescue tube was at Anini Beach. Some five people were clinging to the device before they were finally rescued.

Branch Lotspeich and John Gillen with the red memento they bring to Rotary meetings each time another life is saved using a rescue tube

The most memorable rescue, Lotspeich says, was at Hanakapiai Beach. Two boys were swept out to sea with their dad. The older boy was attempting to rescue his younger brother when he also got caught in the current. The father, a visitor from Oregon a doctor and expert swimmer started screaming on the beach for anyone to give him something that floated. A rescue tube was handed to him and he went flying into the water. After reaching his children, he transported them into a cavelike area, dodging what were described as school bus-sized waves, until they were finally rescued some three hours later.

“He said, ‘I knew that if I didn’t have something that floated, there was no way I could have supported my two sons and myself,'” says Lotspeich regarding the dad.

Though the discussion of installing rescue tubes has been under way for many years, the first tube was unofficially hung on a tree at Larsen’s Beach in 2008 by a man named John Tyler. Since then, the Kaua’i Lifeguard Association grabbed hold of the concept, with its members designing and installing around 110 stations across the island.

Historically, more people drown on Kaua’i every year than die by motor vehicle accident, notes Dr. Monty Downs, president of the Kaua’i Lifeguard Association.Hawaii is the drowning capital of the United States, and Kaua’i is the drowning capital of the state, according to Gillen. Since the inception of rescue tubes, however, drownings on-island decreased by half from about 10 per year to five.

Rotarians Lotspeich and Gillen have even taken rescue tubes to another level. The duo latched onto the idea after Kaua’i Lifeguard Association members approached the Rotary Club of Hanalei Bay for funding.

“What Rotary has done is kind of wrap its head around a need. And rather than just throw money at it, we try to muster forces,” says Lotspeich.

“They (Lotspeich and Gillen) jumped onto the lifesaving idea and have hugely supported and expanded it,” says Downs.

Branch Lotspeich is in the process of creating another rescue tube station at the organization's shop

The two-person team is even in the process of installing rescue tube stations on other islands, including Oahu and the Big Island.

“I’ve never been involved in anything before that directly and measurably saves human lives,” says Lotspeich, the foundation’s spokesman. “It’s been just remarkable.”

Gillen is equally gratified to be a part of the success.

“Saving people’s lives is the more important thing that I do,” says Gillen, whose wife, Catherine, is a University of New England professor.

An entrepreneur who owns Aloha Pack, Copy and Storage Centers, Gillen always finds time to invest in rescue tube installation.

Branch and John work with Rotarians at Hanalei Bay Jan. 28 in preparation for the installation of 22 rescue tubes

Lotspeich moved to the island about six years ago and is a retired medical photographer from Ohio. The son of a neurosurgeon and a photography enthusiast, he says, “It was a natural way for me to be involved in medicine.”

Lotspeich, who is also gifted in the technological world and has created several advancements, including a medical media center in China, has even been directly involved in the assembly and creation of the rescue tube stations at the foundation’s shop in Kilauea. He is married to retired social worker Melody, and still enjoys taking photographs as a hobby.

“Branch is one of the kindest men I’ve known,” says Downs, “and also one of the most skilled.”