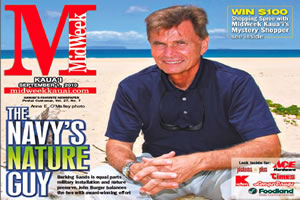

The Navy’s Nature Guy

John Burger

Barking Sands is equal parts military installation and nature preserve. John Burger balances the two with award-winning effort

John Burger wins the Navy’s top conservation award for his work at Barking Sands

John Burger’s nickname is the Energizer Bunny, and within a microsecond of meeting him, you understand why. As environmental coordinator for Hawaii Range Complex Sustainment Support contract headquartered at Barking Sands Pacific Missile Range Facility, he’s got one speed – fast forward.

The U.S. Navy recognized his accomplishments and awarded him for being the best in the Navy at taking care of a base’s natural resources – that is, the best of all personnel at all U.S. Navy bases around the world.

In 2009 for the fiscal year prior, he received the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Cultural Resources Management/Small Installation award as program manager for cultural resources. And this year he received both the CNO and the Secretary of the Navy Natural Resources Conservation/Individual Award for the fiscal year prior.

What are some of the things Burger’s done that make him tops?

He’s charged with the enormous task of caring for the natural and cultural resources of the world’s largest military test range. PMRF is capable of supporting subsurface, surface, air and space activities for the U.S. Navy, other Department of Defense agencies, foreign military forces and private industry.

The surf and turf under discussion is awesome: 7.5 miles of sandy beach and 2,454 acres of land – some of it in remote sites. He’s all over it, literally and figuratively, and says it’s all about cooperative conservation, communication, outreach and education.

John Burger (left) accepts his top award from Adm. Gary Roughead, chief of naval operations

This is the realm of the wedge-tailed shearwater and Laysan albatross, protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and of the endangered native Hawaiian monk seal and threatened green sea turtle, protected by the Endangered Species Act.

This is where two green sea turtles nested for the first time in more than a decade, and the turtles hatched just three weeks ago. When DLNR aquatic biologist Don Heacock and Burger dug up the first nest, they found healthy babies ready to strike out on their own voyage of discovery into the vast ocean. The second nest hatched successfully, too.

“If I died and went to heaven, it would be right here,” says Burger, now in his sixth year working at PMRF. “For a biologist, this place has more to offer than anyplace I can imagine.

“I’m working for the Navy in a place that’s not a national park, so we don’t have to deal with the public, just with natural resources.”

How Burger goes about his job is what garners him awards and the respect of environmental agencies from the feds to the locals. It’s inter- and cross-agency teamwork that yields cooperative conservation.

For example, PMRF, just like any airfield, needed to reduce the Bird/Animal Air Strike Hazard, in particular from the Laysan albatross that tends to nest close to the flightline. The birds have nest fidelity – and a life span of some 60 years.

“The Laysan has a 6-foot wingspan and although it is a lightweight bird for its size, it is a very large amount of bird that can do damage to a windshield, wing or engine at the speed of contact,” says Burger. “Through a wind-shield, it would almost certainly be fatal to a pilot, who would be struck in the face.

“They cruise over the runway during daylight hours and prefer the same area of the base where the active runway is located, and it’s no coincidence – the air currents are right for both the Laysan and the aircraft.”

Burger hacks back a kiawe tree with volunteer Keli Kleidosty (left) and intern Rachel Martin

The Navy is within its rights to contract for the killing of animals that endanger airfield safety in its mission, even for a seabird protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

How to mitigate the situation?

In cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s Kilauea National Wildlife Refuge, Burger began a Laysan Albatross Surrogate Parenting Program in 2005 that continues to this day and has a hatchling success rate similar to that of chicks hatched by their biological parents.

Yet a third federal agency, the USDA Animal Plant Health Inspection Service’s Wildlife Services, each season moves approximately 25 eggs from the PMRF to nests at Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge, where albatross foster parents continue the sitting, straight through to hatching. And the chicks seem to get the imprint to return to KNWR, not PMRF.

In another example, two colonies of wedge-tailed shearwaters nest at PMRF, one of them on a sand dune cliff face and one within a recreational complex of beach cottages. As they expanded their turf, the cottage birds began creating hazards by undermining structural foundations.

The Navy built a three-sided, 6-foot-high wooden fence facing the beach, then buffed up the nest to upgrade an area where the soft earth easily collapses and could doom birds to an early burial.

On the day of this interview, Burger has a couple of volunteer interns hacking the invasive, thorny kiawe tree to bits, removing its roots and pulling out the invasive golden crown beard plant. Both species create difficulty for the birds; in their place, the indigenous naupaka grows exactly where it belongs.

He’s also worked with the Kaua’i Invasive Species Committee in the eradication of long-thorn kiawe, another invasive variety of kiawe that is of particular concern on Kaua’i.

The diversity of Burger’s efforts is impressive: coordinating and supporting across four agencies everything from local to federal on a necropsy of a humpback whale calf to an amazing tale of a turtle that received surgery on a wound received after being struck by a small-craft propeller.

A Laysan albatross tends to its egg and nest

In the case of the former, PMRF public affairs officer Tom Clements lauds Burger, saying, “Bottom line for the success of the event can be credited to John’s networking relationships. Because of that established relationship, the idea, then decision, then action to create a perfect necropsy location took less than a couple of hours to achieve – pretty good for a group that included federal, state and county involvement.”

And for the surgery, the turtle that earned the nickname “Ding” that captured media attention, the work was again accomplished across agencies, and, says Burger, “The beauty of the story is, I wasn’t here!” It’s a fact he’s proud of, seeing evidence that the network he’s been building is totally operational.

His job brings great joy to Burger, who looks at the ways the Navy is helping the environment.

“For example, for the last five years, the Navy has killed more than 100 barn owls, predators of the bird colonies. At nighttime, for owls, it’s like going out to a supermarket and taking the food right off the shelf – owls pounce on the wedge-tailed shearwaters on the ground and eat their organ meat.

“I want to present information about what science and the Navy are doing and show it’s not all one-sided.”

He advises people to “try to get all the facts about the environment before taking a stand – there’s so much misinformation and disinformation out there.

This was the first time in more than a decade that green sea turtles nested at Barking Sands

“The way it’s presented by people, you’d think it’s only wire and lights that are the problem [for birds]. But we don’t know. We want to do more conservation research.

“We have so much cultural resource work that could be done here. We protect the resources, but don’t know the full extent of what we really have.

“We’re really stewarding the environment and at the same time ensuring that the Navy is doing its mission. I think we’ve made a case through the Navy that we could use some more professional resources – for example, get a full-time wildlife biologist, a full-time archaeologist.”

The outdoors holds so many perks for Burger, an active person, but the job demands desk time as well.

Rising at 5 a.m., chowing down in his home in Wailua Homesteads and getting a java fix, Burger heads to PMRF in his VW van to “start computer wars,” as he calls it. Once in the office, it’s the land of ACRONYMIA.

These days Burger is giving one acronym a great deal of attention. It’s an EIS, or Environmental Impact Statement that he and scores of others are working on.

As is the case with all federal agencies, PMRF is subject to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969 that sets up procedural requirements for stating the environmental impacts of its actions. Whatever is planned on the range – and it’s huge, filling 1,300 pages in the last EIS incarnation – must take into account what happens with the natural and cultural resources on the base.

“In scoping meetings, we’re getting public input to analyze what’s going on out on the range,” says Burger. “The EIS is for all training and testing in the ocean in Hawaii and Southern California and the transit zone in between.

“People have a lot of concerns because they don’t know what the Navy does. We listen to their concerns and show the public pictures and stories, and they say, ‘I didn’t know you did this.’ The fact that we have a marine reserve, have threatened animals come here, people don’t know what we do – they presume we’re just launching missiles and making trouble.”

Burger estimates the EIS will take two to three years to complete and will draw on a lot of public input.

“We send drafts to all sorts of agencies for review. They take their specific area of responsibility that they may be concerned with and can voice their concerns.”

John and Mary Burger with son Jonathan, his girlfriend Jusefine Alop and Chieftan the Chihuahua

Drafted into the U.S. Army right out of college, Burger did a tour of duty in Vietnam where he was supposed to teach radar repair that he’d just learned himself, only when he got to his duty station there was no radar. His work evolved into administration, and when he finished his service, he enrolled in Rutgers University, majoring in environmental science.

“I always wanted to be a practical field biologist,” says Burger. “I’d applied to the federal government, the park service, forest service – but I got nowhere.”

Collecting a master’s in environmental science in 1975, Burger was on his way. And on the path, he met and married Mary Jane Burger, his wife of 39 years. The couple has two grown adopted children, Jonathan, 37, and Lucy, 28, both of whom live in Hawaii.

MJ, as Burger calls his wife, retired from a career in teaching special education and has a private practice here as a certificated learning disabilities teacher consultant.

By the time Burger reached Barking Sands in 2002, he says he’d had a long career in performing the “industrial side of the Environmental Protection Agency business where you try to clean up after the fact.”

His job here, he says, “is as much to protect the resources we have as it is to respond to people who want to regulate, to help them understand what we’re doing. We’re doing sustainment through the process of working with agencies.”

To learn more about the EIS or natural resources at Barking Sands PMRF, contact Burger at 335-4632 or john.burger1.ctr@navy.mil.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There are no comments

Add yours