‘Jeopardy!’: Man Loses To Machine

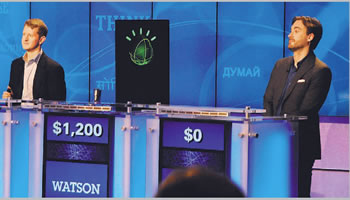

‘Watson’ beats Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter with ease on ‘Jeopardy!’

Over the past four years, a team of IBM scientists set out to build a computing system that rivals a human’s ability to answer questions posed in natural language with speed, accuracy and confidence. The result is a computer named Watson. This is not your “typical computer” built to beat you at a game of chess – try a game of Jeopardy!

From Feb. 14 to 16, Watson competed on Jeopardy! against Ken Jennings (who won 74 straight rounds of Jeopardy!) and Brad Rutter (who retains the record for Jeopardy! winnings – $3.2 million). As you’ve no doubt heard by now, Watson totally dominated Jennings and Rutter, finishing the three games with a total of $77,147, more than the two humans’ $24,000 (Jennings) and $21,600 (Rutter) combined.

So what exactly is Watson? On stage it’s a large LCD monitor with a sphere-shaped avatar, but in reality it’s a massive collection of servers functioning as a supercomputer. These servers consist of 100 IBM Power 750 server units and are housed in 10 server racks in a room next to the Jeopardy! stage, not to mention it is equipped with 15 terabytes of onboard RAM. Basically Watson is as powerful as 2,800 powerful computers combined.

Jeopardy! provides the ultimate challenge for Watson because the game’s clues involve analyzing subtle meaning, irony, riddles and other complexities in which humans excel and computers usually do not. Watson’s ability to understand the meaning and context of human language, and rapidly process information to find precise answers to complex questions, holds enormous potential to transform how computers help people accomplish tasks in business and their personal lives.

Watson isn’t connected to the Internet, so any information it draws from was loaded into Watson by IBM engineers. It is competing against two people that basically know everything, but amazingly, Watson can analyze a clue delivered in conversational English and come up with an answer with the analytical engine. While watching these Jeopardy! episodes, you’d see Watson’s three possible answers (with probability percentiles) pop up at the bottom of your TV screen, along with its spinning avatar to show it thinking.

On all shows, Watson answered the questions so quickly that Jennings and Rutter barely had a chance to buzz in. It was a trivia bloodbath. However, for Final Jeopardy on the second show, the category was U.S. cities, and they were asked to name the city that has one airport named after a World War II hero, and another named for a

WWII battle. Here is where Watson failed. The correct answer is Chicago, which Jennings and Rutter both answered correctly, and Watson answered “Toronto???”

Taking a look at its wrong answer, we see that Watson did not consider the restrictions set by the category itself. Watson only wagered $947, likely realizing it could still win. Watson’s strength is that it doesn’t have to worry about forgetting anything. As an emotionless machine, it can buzz in more quickly than the other contestants, as it computes the question factors with a numerical pre-

ciseness that humans cannot. But Watson’s weakness is its confusion with complex sentences (i.e. when contestants are asked to consider two indirectly related factors or ideas). Its confidence goes down, and the reaction times are slower. Additionally, it seems Watson doesn’t know anything about the arts. It reacted slowly to the art-related questions, and the one it answered correctly, the confidence level was only 32 percent.

It will be interesting to see if this will pave the way for the future of man versus machine …

Overall, Watson was made to enable people to rapidly find specific answers to complex questions. The technology could be applied in areas such as health care for accurately diagnosing patients, to improve online self-service help desks, to provide tourists and citizens with specific information regarding cities, prompt customer support via phone and much more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There are no comments

Add yours