The Bird Man Of The Garden Isle

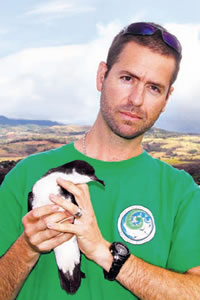

Andre Raine prepares to release a shearwater the morning after he found it

When Andre Raine, Ph.D., isn’t rescuing Kaua’i’s native birds, he’s spreading the message about their fragile existence and their importance

He combs unchartered territory to study Kaua’i’s endangered seabirds.

“This is the last refuge for this species on the planet,” says Kaua’i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project’s Andre Raine about Newell’s shearwater (‘a’o) whose population has declined some 75 percent in the last 15 years.

His team traverses parts of the island accessible only by helicopter to learn more about the elusive birds and their individual colonies and nesting behaviors.

They also spend time researching the Hawaiian Petrel (‘Ua’u) and BandRumped Storm Petrel (‘Ake;’ake;), who are even more difficult to locate and are so small that a nest has yet to be discovered.

All three species are affected on their first evening journey to sea by obstacles that include bright lights that they mistake for the moon and power lines. Though there is a program during the fledgling season (currently under way) at the Kaua’i Humane Society, Save Our Shearwaters, that helps rehabilitate downed birds, there is no evidence yet of their survival rate and the chance of finding the tiny petrels has proven to be extremely difficult.

But more detailed information is hopefully forthcoming.

When the Kaua’i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project first started some six years ago, scientists didn’t even know if petrels were located on the island, and they hadn’t yet found where Newell’s shearwater nested.

Kumo Sabra Kauka releases a shearwater at Lydgate Beach as students from Island School observe. Photo from Andre Raiane

Until recently, the state Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Forestry and Wildlife project, administered by the University of Hawaii, largely focused on understanding the distribution of the species around the island.

Now biologists are attempting to track the patterns of Newell’s shearwaters out at sea using tiny devices tagged to their legs. The information about the seabirds will help determine how many actually survive fledgling season each year and what various mitigation efforts such as shielded stadium lights and predator control have on their population.

When they spend their first four to five years of life at sea and come back only once a year to lay one egg, the importance of successful breeding, nesting and fledging is obvious.

The project’s studies are also able to provide advice and point people in the proper direction regarding issues like habitat management.

Kaua’i has such potential in terms of conservation because it still has seabirds in relatively healthy shape compared to the other islands, says Raine, the project’s coordinator.

“But then on the flip side, although we’ve got a lot of them, their populations are declining really rapidly, so something really needs to be done,” says Raine who has a 2-yearold son Callun with his wife Helen, who was expecting a daughter any day as MidWeek Kaua’i went to press.) “It’s a really catastrophic decline.”

Without the birds, not only is the cultural connection between Hawaiian fishermen who use the birds to locate food lost, but also the ecological impact could be felt in ways that are yet unknown.

“It’s a very much interconnected thing between the birds, the sea and the land, and if you take that out of the equation, you never know what’s going to happen,” says Raine, who earned his Ph.D. at the University of East Anglia studying the twite, a type of finch located in England.

Seabirds also have “every right to exist on this planet as we do,” he adds.

And it is not about birds versus humans.

“Everyone can do the things that they want to do while at the same time enjoying another creature that’s living on the planet and sharing the resources like us,” he says. “We can still do what we want to do while at the same time assuring that these species continue to survive.”

Until mid-December, anyone who finds a downed bird can take it to SOS locations throughout the island, including Lihue and Princeville fire stations.

“It’s quite a sad thing to see when you have these little fledgling birds which have gone through all this up in the mountains and then they end up on a road somewhere or sitting next to a warehouse wall,” says Raine, who has spent many years studying seabirds, including the European Storm Petrel.

To help spread awareness about the importance of the seabirds to Kaua’i, Raine also makes time to educate keiki.

“It’s all about the next generation, really,” he says. “We save the birds so that they’re here for the next generation. They’re the ones who are going to become responsible for them. If they’re learning about them when they’re young, then that gives them the education that they need to conserve them for the future.”

Children attended a blessing ceremony last month where fledgling birds rehabilitated by the SOS program were released at Lydgate Beach for a second chance at life.

“You can really see how excited they are to see the birds,” he says.

“There’s something pretty special about a bird that spends all its life out at sea and then comes into land at night to breed up in the mountains,” says Raine. “We need to be working toward stopping them from disappearing all together.”

Visit kauaihumane.org/services/saveourshearwaters for more information about rescuing downed seabirds.