Galápagos Deal With Tourism Rise

The volcanic Galápagos Islands, 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador, have had permanent human habitation only since 1833.So their 30,000 residents have an opportunity to take charge and not become Hawaii with high-rise beach-front hotels, houses on every hillside, too many cars and half the endemic fauna and flora extinct or endangered.

But that’s a tall order. Santa Cruz Island, the most populated, has jumped from 1,580 to 17,000 residents in just 40 years. The principal town of Puerto Ayora has shouting tour signs, nightclubs, billboards and periodic traffic jams.

The Galápagos will get about 170,000 tourists this year. An ugly concrete hotel is rising in the pristine highlands of Santa Cruz.

But, like us, if you don’t do tourism, what do you do?

The Galápagos are not self-sustaining. Tourism funds protected-park status for endemic birds, marine iguanas, sea lions, penguins and giant tortoises you can walk right up to.

(The water teems with uhu – parrotfish – but residents consider them poor eating!)

Lindblad Expeditions’ position is: “Does tourism positively impact Galápagos? Most definitely! Tourism provides jobs in lodging, transport, food service and retail sales.”

Much of the money, however, goes to outside entrepreneurs. Most tourists sleep and eat on cruise ships.

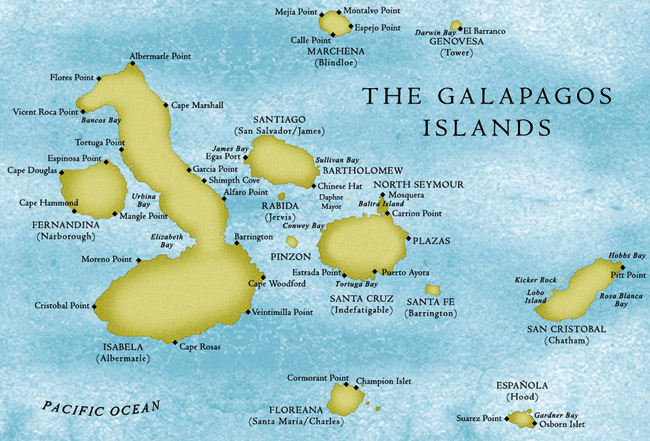

The Galápagos are 21 islands and 107 rocks. Fifteen years ago, Ecuador gave it more autonomy but lowered guide (required) credentials to a high school education and some English. Journalist Carol Ann Bassett says she’s encountered creationist guides who tell you Earth is 6,000 years old and God put humans and animals on it in their present forms.

Outside investors squeeze out locals to run shops, tours, hotels and restaurants.

There’s constant friction between residents and the National Park (97 percent of the land) over fishing limits and who can bring in a pet or a car – lots of “local politics.”

There are new wind turbines on two islands to cut back on oil tankers – one had leaked badly – but that means some visual blight and bird kills. Tough choices.

The islanders must make many tough choices, just as we do. If they cut back tourism, they lose revenue. If they want 8,240,000 tourists a year like us, they make money but suffer the environmental consequences.

And like us in minimally home-ruled Hawaii, Galápagueños are at the mercy of the lawmakers in the capital of Quito to give some of the tourist-tax money.

One of the originators of Galápagos tourism, Sven-Olaf Lindblad, said, “In the end it will be the passion and insistence of the visitor that will ensure the preservation of the Galápagos.”

But the passion of great numbers of visitors to go there and be entertained rather than just lectured on conservation also greatly could diminish the place and turn it into a Waikiki, a Lahaina or a Kailua-Kona.

Very delicate balancing is required.

BanyanTreeHouse@Gmail.com