Steady and True

John Kruse and the Na Mahoe at Nawiliwili Harbor

An original crew member aboard Hokulea, John Kruse is today the pillar of paddling Kaua’i. He’s currently at work on the Garden Isle’s own sailing canoe, Na Mahoe

That’s John Kruse, like the ‘kua’ of a canoe. An original crew member on Hokule’a, he is now building Na Mahoe, a sailing canoe for the people of Kaua’i

If you were to liken John Kruse to a part of one of the canoes he builds, he’d be the kua or “spine” – sturdy and true.

The pillar of Kaua’i’s canoe-building ‘ohana, Kruse has a way of making nearly every sailing anecdote an adage.

A Hawaii treasure, Kruse, one of the sailors on Hokule’a’s maiden passage to Tahiti, has spent much of his life sailing, and now continues to build sailing canoes as part of Kaua’i’s wayfinding legacy. To him, voyaging means the world.

For Kruse, who lost wife Keani years ago to cancer and whose son Kepa lives on the Mainland, working on the canoe keeps him going.

“She was one powerful wahine,” Kruse says of his wife. “My son always asks me, ‘Are you going to find another woman?’And I say, ‘I did it once. I’ve got to keep focused on the canoe.'”

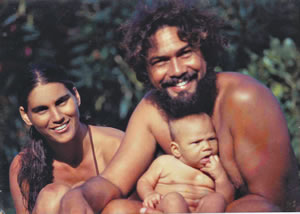

An undated photo of Keani, John and Kepa Kruse

Currently, – and for the past 15 or so years – “canoe” references Na Mahoe, the 72-foot double-hulled sailing canoe that Kruse, Marshall Mock, Dennis Chun and the late Dr. Patrick Aiu conceived so that Kaua’i and Ni’ihau would have a traditional voyaging canoe of their own.

Of course, “Hoku,” as they affectionately refer to the Hokule’a, has a history here on Kaua’i and has a standing Kaua’i crew, though the canoe’s home base is on Oahu.

“The Hokule’a was in all the Islands, but is kind of Oahu’s, and they’re really protective of the Hokule’a – rightly so,” Kruse says.

Kruse, who has been involved with the Polynesian Voyaging Society through its initial successes, tragic missteps and triumph through adversity to become the icon of Hawaiian culture it is today, is a founder of Na Kalai Wa’a o Kaua’i, the group building Na Mahoe.

It’s important to say group, Kruse says, as it’s not just one person who makes the success of building and caring for a sailing canoe possible.

Aiu conceived the name Na Mahoe, which translated means “the twins,” referring to the Gemini constellation that guided voyages between Kaua’i and Oahu.

Following the lead of the Big Island’s Clay Bertleman and Na Kalai Wa’a Moku o Hawai’i – the group that built that island’s voyaging canoe, Makali’i – once the name Na Mahoe was chosen, the Kaua’i daughter of Hokule’a was born.

And so in Hokule’a’s wake follow four new voyaging canoes.

Since its initial voyage to Tahiti in 1976, Hokule’a and the art of wayfinding have been a touch-stone, a symbol of what Hawaiians and Polynesians could accomplish and a metaphor for the Hawaiian culture.

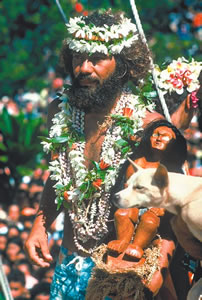

Thousands were excited to greet Hokule‘a in Tahiti; John Kruse is in there somewhere

Perhaps one of the most dense metaphors of the canoe to Hawaii is in the concept of ohana. The crew is family. The association of voyaging canoes is family. The canoe is one’s mother when one is voyaging, and caring for the canoe takes the whole ‘ohana.

“The desire to be with the canoe is pretty strong,” Kruse says. “It can bring people together and pull them apart, because you’re in the modern world but trying to look back into your past to find out what other people before you did. You’ve always got your ancestors behind you. Whatever you do or say, good or bad, they’re behind you – same like the canoe, an embodiment of those kine values from the old, the past.”

It’s to capture a glimpse of that incarnation that brought families out to watch those who were working on the Hokule’a back in the day, Kruse says.

“When we built the canoe, it touched everybody,” he says. “Families would come to watch us work and be staring at the canoe because, to them, it was the embodiment of what their elders told them.”

With the Hawaiian Renaissance came the birth of the Polynesian Voyaging Society in 1973, reconnecting local people with the wayfinding tradition mastered by Polynesians some 800 years ago.

Since Hokule’a’s first voyage, which was navigated by master Micronesian navigator Mau Piailug, the art of wayfinding has become stronger in Hawaii. Before he passed away, Piailug initiated five of his Hawaii students into Pwo, a master navigator status, and the list of Hokule’a’s crew now spans generations.

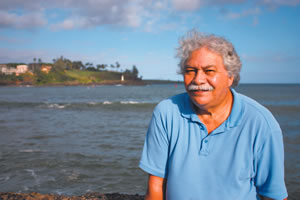

Kruse with a fresh catch aboard Hokule‘a

Piailug navigated the trek from Honolua to Tahiti just by watching and reading the stars, the rising and setting of the sun and the way the waves broke across the canoe.

It was in the darkness that Piailug would often sit, Kruse recalls, alluding to one particular instance when, without his knowledge, his son Kepa wandered off with Piailug.

Kepa was still small at the time, and Kruse had tied him to himself with a rope so that he wouldn’t wander off while they were asleep below deck. Kruse said he woke up only to find nothing attached to the other end of the rope.

“I found him. He was with Mau, happy, in the darkness,” he says.

Perhaps that anecdote exemplified the sheer trust and admiration Kruse and others felt for Piailug.

“I think that first crew that went to Tahiti, we were all like a wolf pack,” he says. “All wolves have the alpha wolf, and the alpha wolf was Mau. All the other wolves, we respected him for that. Here you had this guy showing what it was like for our ancestors in the past.”

After 31 days approaching the island of Mata’iwa until finally getting to Papeete in Tahiti on day 32, the land-starved crew was excited when clues began surfacing that they were getting close.

Kruse says before they could see land, Piailug pointed out where the seas went flat and the swells were backwashing from enveloping the island.

“You gotta be real good to know that,” Kruse says.

“The animals smelled the land, too, and the animals were going off,” he says. “Then we started to see rubbish in the water, and it was like ‘eh, rubbish!'”

Kruse in Papeete with the ki‘i from the rear of Hokule‘a

Mata’iwa residents knew the canoe was coming but didn’t expect it to land on their island, noting the arrival was a tad anticlimactic. However, the celebration once they landed in Papeete was anything but.

“When we finally got to the beach, it was crazy,” Kruse says. “That’s when so many people came on the canoe, it sank in four feet of water.”

It was an emotional landing, as the voyage had been. There was a lot at stake, including demonstrating that this kind of venture was even possible, that the Polynesians did in fact cross thousands of miles in voyaging canoes.

“This was the first time – in 1976 – this had been done for 800-plus years,” Kruse says. “The more we did it, well, the more we got confident.” That confidence came from the simple knowledge gained in terms of what necessitated a good crew.

“We had good fishermen, lots of water and a crew you have to trust in because your life is in their hands,” he says. “You’ve gotta be one.”

That fragility of life and the risk the Polynesians took time and time again were perhaps brought into glaring reality during that next voyage when Hokule’a capsized – when Eddie Aikau, who went in search of help on a surf-board, was lost at sea.

“I remember when we flipped over and were sitting there in the water in the evening,” Kruse says. “I thought, wow. My idea was we’re all going to get there together or we’re all going to die together. The main thing is, when you die, you’re with your family.”

After the canoe swamped, it was rebuilt and sailed in 1980 in honor of the Aikau family.

When Na Mahoe is completed, Kruse has another canoe in mind

Of course, the many trips that followed resulted in increased confidence among crewmembers – especially when being at sea necessitated improvisation, such as the time utensils were left on shore.

“I remember we had coconut and consequently forgot all the utensils,” Kruse says. “So we had to make coconut bowls to eat from.” The crew also made crude chopsticks. “It was real Survivor show-kine stuff,” Kruse says. “And it was like, ‘Eh! Boogie (George) Kalama’s coconut stay bigger than mine! He’s getting more food!'”

Kruse says his years on the canoe were full of anecdotes like that, which is what made each voyage distinctive.

On one such trip in the ’90s, Nainoa Thompson’s classmate Lacy Veach, a NASA astronaut, was communicating with the Hokule’a via the Mars station, which relayed back to the canoe while he was orbiting Earth on the Space Shuttle Columbia.

“We were using the ancient way of sailing (130 miles at 5.5 knots) and they were going 18 miles above the earth at 13,000-15,000 miles an hour,”

Kruse says.

“Every 45 to 50 minutes, they would check the earth. We’d say, ‘Eh, do you see any clouds?’ And Veach was looking at the bottom of South America, and clouds were coming around South America into the Pacific.”

Beyond the initial voyage, Kruse – who says he’s been on Hokule’a too many times to count – sailed to Aotearoa (New Zealand) on the Ku Holo Mau voyage, which brought the newest voyaging canoe at the time, the Alingano Maisu, to Piailug in Satawal.

“One of the times we went to see Mau, and gifted him the (Alingano) Maisu, the new canoe, he reiterated in the pwo initiation ceremony that crews can disagree, but should always work together,” Kruse says.

Explaining the background of the pwo ceremony, Kruse adds that when they went to Satawal, Piailug’s native 1.5-mile-long, 1-mile-wide island, it was clear that navigating wasn’t about resurrecting culture, but how they feed their people and survive.

“They were all people within Mau’s influence, and it’s more than about non-instrument navigation,” he says. “He is the leader in the community, who goes out into the ocean to get food to feed the island, be it fish or teaching young people. All that is comprised in that ceremony of pwo because you are trusted to become an ongoing resource in your community. Being at sea is one part, but a leader and feeding your community is another part.”

Piailug told them how to lead so they could continue to do so on Kaua’i.

“If you’re supposed to be a pillar in the community, you set the example. So in our older age, we gotta do that,” says Kruse. “If he told me that 30 years ago, I’d say, ‘Ah, I’m not a kupuna, I’m just an older guy. I think you become an elder if you say you’re getting old, and then you shouldn’t be on the canoe.”

So what’s next for Kruse following the completion of Na Mahoe? Building another canoe, of course.

“I like build another canoe,” he says. “A 56-57-foot canoe.”

With the building of another canoe, just like those built in the past, it will serve as an educational tool.

“When you’re building the canoe, it teaches you life lessons – patience and a tolerance for tedium,” he says.

“As I’m building this new canoe in my older years, when you’re more community-oriented, I’m thinking all what Mau has taught me. Now I can teach Kepa and continue to teach young people who will be the beneficiary of what I’ve learned from Mau.”

Already those teachings are helping keep the tradition alive.

Come June, following the Ocean Noise conference in Honolulu, seven canoes will set sail to Kaua’i from different island nations: From Fiji, the Uto Ni Yalo; from Samoa and Tonga, the Hina Moana and Gaufalo; from the Cook Islands, the Maru Maru a Tua; from Tahiti, Fa-a Faiete; from New Zealand, the Matau Te Maui; and, as part of Piailug’s legacy, from Satawal, the Alingano Maisu, navigated by Piailug’s son, Sesario Piailug.

Quoting a Maori expression, Kruse says of the event and of wayfinding in general, “A te moana kupu takoha tangata hou manawa ora – and the sea will grant men new hope.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There are no comments

Add yours