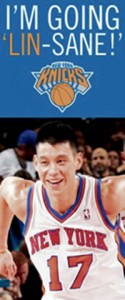

A Linstant Celebrity In New York

It’s been impossible to even casually follow the sports landscape the past few weeks without being overrun with Linsanity.Jeremy Lin, the new starting point guard for the New York Knicks who went unrecruited out of high school, undrafted after attending Harvard and unnoticed for two other NBA teams, took over the news cycle after suddenly dominating opponents and stabilizing a high-profile team in disarray.

Through his first nine games as the team’s starting point guard, Lin was averaging 24.6 points, 9.4 assists and 2.4 steals per contest. If he had been putting up those numbers since the first game of the season, Lin would currently rank fifth in points, third in assists and second in steals among all NBA players.

The rarity of production that incredible is nothing compared to the rarity of an Asian-American playing basketball at the highest level. While some have been hesitant to discuss Lin’s race as an issue, and others have been deservedly reprimanded for making insensitive and offensive racial remarks, to think that Lin’s race has no impact on the enormity of the story is both ignorant and does a disservice to what he suddenly means to many people.

This would be a big deal no matter what Jeremy Lin looked like or where his parents were born, but the 23-year-old is a sight previously unseen to a large population around the globe. There are few who have heard of Wataru Misaka, the first Asian-American NBA player who, coincidentally, also played point guard for the Knicks back in 1948. Since Misaka, just a handful of Asian-American players have donned NBA uniforms and Lin is the first since Misaka whose parents are both of Asian descent.

Even on the college level, fewer than 1 percent of all NCAA Division I players are Asian-American, so a huge group of young athletes just don’t ever see their race represented in one of the world’s most popular sports. Though Yao Ming and other Asian players have come over to the NBA, they did so after establishing themselves as the premier players in a huge country. Lin has come up the ranks in the United States, where he’s had to deal with being disregarded in a way in which I’m sure young Asian-American players can relate.

Usually in sports, people make comparisons based on appearance, rather than substance. In high school, when I would go play basketball at the park with a mostly black group, after I knocked down a jump shot, I’d usually get a nickname like Steve Kerr or Wally Szczerbiak. It didn’t matter that Kerr’s shot had a lower release point or that Szczerbiak had more of a set shot they were white and so was I. (Still am.) One of my proudest moments on the court was on a day when my jumper was particularly percolating, hearing one of the guys call me Ray Allen. Breaking the nickname color barrier is a big deal.

In this day and age, race is rarely the sole factor in sports. If you can play, you can play. That’s why despite the road blocks in his way, Lin is less of a “Linderella” story than further proof that the cream rises to the top. No college offered him a scholarship, so he went to Harvard and played great. No team drafted him, so he went to the summer league and played great. He got very little opportunity with the Warriors or Rockets, but he got a chance with the Knicks and has played great.

Talent plus opportunity equals success.

While his race isn’t important to his teammates or his opponents anymore, it is important to a lot of young players who now have a figure who resembles them to look up to. I’m sure it will be tiresome for good young Asian-American players to get the Jeremy Lin nickname treatment at the playground from now on, but they may get a second look from scouts who would have previously quickly moved on.

Lin has likely provided many with talent increased opportunity.